Psoriatic Arthritis of the Knees: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

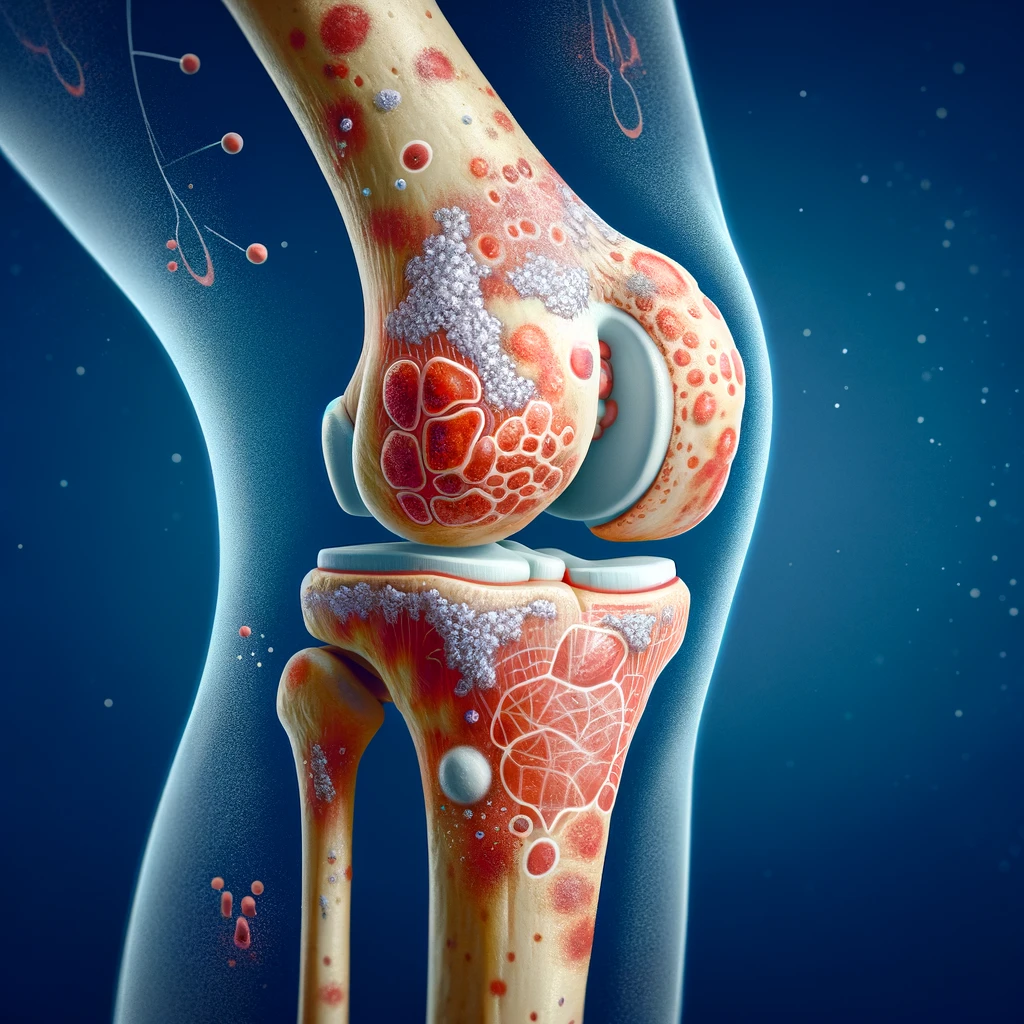

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes inflammation in the joints and skin. It is a type of arthritis that affects people who have psoriasis, a skin condition that causes red, scaly patches on the skin. Psoriatic arthritis can affect any joint in the body, including the knees, and can cause pain, stiffness, and swelling.

Psoriatic arthritis of the knees can be particularly debilitating, as it can affect a person’s ability to walk, climb stairs, and perform everyday activities. The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis in the knees can vary from person to person, but common symptoms include pain, swelling, stiffness, and difficulty moving the knee joint. It is important to diagnose and treat psoriatic arthritis of the knees early on to prevent further joint damage and improve quality of life.

Key Takeaways

- Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic autoimmune disease that affects people who have psoriasis.

- Psoriatic arthritis of the knees can cause pain, swelling, stiffness, and difficulty moving the knee joint.

- Early diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis of the knees is important to prevent further joint damage and improve quality of life.

Understanding Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, inflammatory arthritis that affects people who have psoriasis. Psoriasis is a skin condition that causes skin cells to build up and form plaques—dry, itchy patches of skin. PsA can cause pain, stiffness, and swelling in the joints, including the knees.

PsA is an autoimmune disease, which means that the immune system attacks healthy cells in the body. In PsA, the immune system attacks the joints, causing inflammation and damage. Over time, this can lead to joint deformities and disability.

PsA is a chronic condition, which means that it lasts for a long time—often for the rest of a person’s life. However, with the right treatment, many people with PsA can lead full, active lives.

The goal of treatment for PsA is to reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and prevent joint damage. There are several types of medications that are used to treat PsA, including disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and biologics.

DMARDs are a type of medication that can slow down the progression of joint damage in PsA. They work by suppressing the immune system, which reduces inflammation in the joints. Some common DMARDs used to treat PsA include methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide.

NSAIDs are a type of pain reliever that can help reduce inflammation and relieve pain in the joints. They are available over-the-counter or by prescription, and include drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen.

Biologics are a type of medication that are designed to target specific parts of the immune system that are involved in inflammation. They are given by injection or infusion, and include drugs like etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab.

In addition to medication, there are other treatments that can help manage the symptoms of PsA. Physical therapy and exercise can help improve joint mobility and reduce pain. Lifestyle changes, such as maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding smoking, can also help reduce inflammation and improve overall health.

Overall, PsA is a chronic condition that can cause pain, stiffness, and swelling in the joints, including the knees. However, with the right treatment, many people with PsA can lead full, active lives.

Psoriatic Arthritis and the Knees

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a type of inflammatory arthritis that can affect many joints in the body, including the knees. PsA is a chronic autoimmune disease that can cause joint damage, leading to stiffness, swelling, and pain. It can also cause tendons and ligaments to become inflamed, making it difficult to move the affected joints.

When PsA affects the knees, it can cause significant discomfort and make it difficult to walk. Knee pain is a common symptom of PsA, and it can be accompanied by stiffness and swelling. In some cases, PsA flares can cause such severe pain that walking becomes nearly impossible.

PsA can cause joint damage over time, leading to permanent disability. It’s important to seek medical treatment as soon as possible to prevent joint damage and manage symptoms. Treatment options for PsA of the knees may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce pain and inflammation, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) to slow the progression of the disease, and biologic medications to target specific parts of the immune system.

In addition to medical treatment, there are also lifestyle changes that can help manage symptoms of PsA and improve overall joint health. Maintaining a healthy weight, staying physically active, and avoiding activities that put excessive stress on the knees can all help reduce symptoms and prevent further joint damage.

In conclusion, PsA can affect the knees and cause significant pain, stiffness, and swelling. It’s important to seek medical treatment and make lifestyle changes to manage symptoms and prevent joint damage. With proper treatment and care, it’s possible to live a full and active life with PsA.

Symptoms of Psoriatic Arthritis in the Knees

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic autoimmune disease that affects millions of people worldwide. It is a type of arthritis that can cause inflammation and pain in the joints, including the knees. Here are some of the common symptoms of psoriatic arthritis in the knees:

- Pain: Joint pain is one of the most common symptoms of psoriatic arthritis in the knees. The pain can be mild to severe and can be felt in one or both knees. It can also be felt in other joints in the body, such as the hips, ankles, and wrists.

- Swelling: Swelling and inflammation are also common symptoms of psoriatic arthritis in the knees. The swelling can be mild or severe and can make it difficult to move the knee joint.

- Stiffness: Stiffness in the knee joint is another common symptom of psoriatic arthritis. The stiffness can be worse in the morning or after periods of inactivity. It can also be caused by inflammation in the knee joint.

- Flares: Psoriatic arthritis can cause flares, which are periods of increased joint pain, swelling, and stiffness. Flares can be triggered by stress, illness, or other factors.

- Fatigue: Fatigue is a common symptom of psoriatic arthritis. It can be caused by the inflammation in the body and the stress of living with a chronic condition.

- Tenderness: Tenderness in the knee joint is another symptom of psoriatic arthritis. The knee joint may be tender to the touch, and it may be painful to put weight on the affected leg.

If you are experiencing any of these symptoms, it is important to talk to your doctor. Your doctor can help you manage your symptoms and develop a treatment plan that works for you.

Diagnosis of Psoriatic Arthritis

If you suspect that you may have psoriatic arthritis, it is important to see a doctor who specializes in rheumatology. A rheumatologist can diagnose psoriatic arthritis based on your medical history, physical exam, and certain tests.

During the physical exam, the doctor will look for signs of psoriasis, such as red, scaly patches of skin. They will also examine your joints for signs of inflammation, such as swelling, warmth, and tenderness.

To confirm a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, the doctor may order certain tests, including blood tests, X-rays, MRI scans, and ultrasounds. These tests can help the doctor determine the extent of joint damage and rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms.

One blood test that may be ordered is the rheumatoid factor (RF) test. This test can help distinguish between psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. While RF is often present in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis, it is not typically present in people with psoriatic arthritis.

An X-ray can show joint damage and bone loss, while an MRI can provide more detailed images of the joints and surrounding tissues. An ultrasound can also be used to visualize inflammation in the joints.

Overall, the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis can be challenging because it shares many symptoms with other types of arthritis. However, with the help of a rheumatologist and various diagnostic tests, a diagnosis can be made and appropriate treatment can be started.

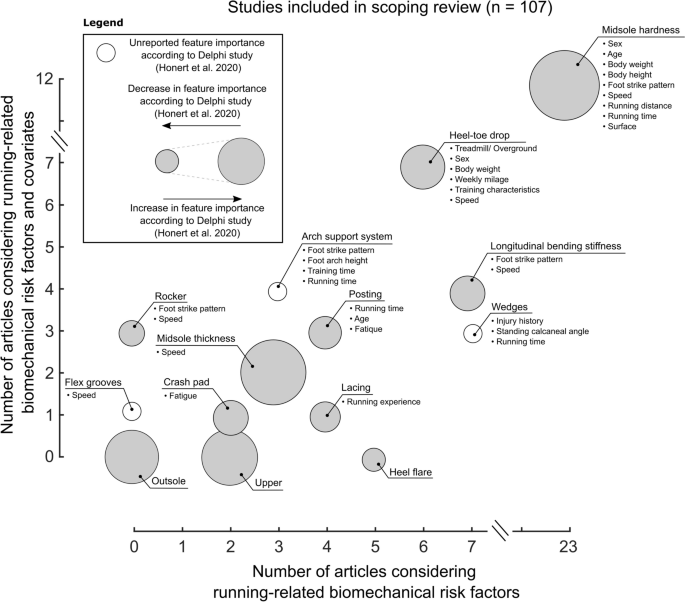

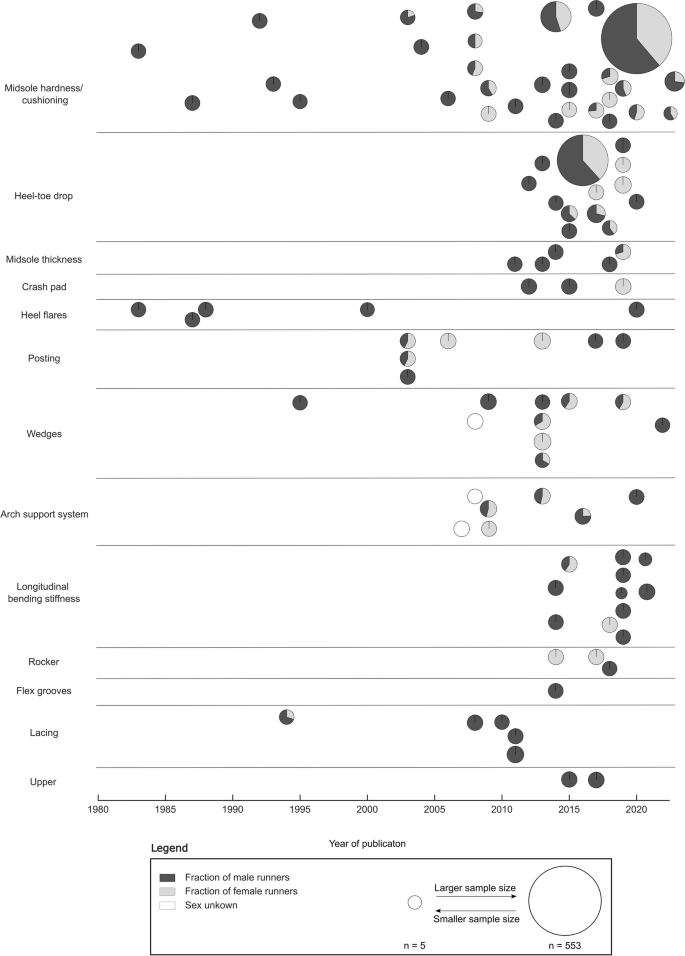

02 Tables

Tables can be a useful way to display information about Psoriatic arthritis of the knees. Here are some examples of information that can be displayed in tables:

- Symptoms: Common symptoms of Psoriatic arthritis of the knees include pain, stiffness, swelling, and warmth in the joint. Other symptoms may include fatigue, nail changes, and eye inflammation.

- Diagnosis: A diagnosis of Psoriatic arthritis of the knees may involve a physical exam, blood tests, imaging tests (such as X-rays or MRI), and joint fluid tests.

- Treatment: Treatment for Psoriatic arthritis of the knees may involve medications (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, or biologic agents), physical therapy, and surgery (in severe cases).

- Prevention: There is no known way to prevent Psoriatic arthritis of the knees, but maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding smoking, and managing stress may help reduce the risk of developing the condition.

Tables can also be used to compare different treatment options for Psoriatic arthritis of the knees, such as the benefits and risks of different medications. It is important to discuss treatment options with a healthcare provider to determine the best course of action for each individual case.

In addition to tables, bullet points can be used to summarize key information about Psoriatic arthritis of the knees. Bold text can be used to highlight important terms or concepts, making it easier for readers to quickly scan the information and find what they are looking for.

Overall, tables and other formatting tools can be a helpful way to present information about Psoriatic arthritis of the knees in a clear and organized manner.

Causes and Risk Factors

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a type of inflammatory arthritis that can develop in people who have psoriasis. The exact cause of PsA is not yet known, but research suggests that it may result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and immune system factors.

One of the main risk factors for developing PsA is having psoriasis, a chronic autoimmune skin disorder that causes red patches of skin topped with silvery scales. In fact, up to 30% of people with psoriasis may develop PsA. The severity of psoriasis does not necessarily predict the development of PsA.

Age is another risk factor for developing PsA, with most people being diagnosed between the ages of 30 and 50. However, PsA can occur at any age, including in children.

Family history is also a significant risk factor for PsA. People with a family history of PsA or psoriasis are more likely to develop the condition themselves.

Certain environmental factors, such as smoking, obesity, and stress, may also increase the risk of developing PsA. Infections, particularly those caused by streptococcal bacteria, may also trigger the onset of PsA in some people.

PsA can also be associated with nail disease, such as nail pitting or separation from the nail bed. In some cases, PsA can also be associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

In conclusion, the exact cause of PsA is not yet known, but research suggests that it may result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and immune system factors. Having psoriasis, a family history of PsA or psoriasis, and certain environmental factors may increase the risk of developing PsA.

Effects on Other Body Parts

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects not only the joints but also other parts of the body. In addition to joint pain, swelling, and stiffness, psoriatic arthritis can cause a range of symptoms in different body parts.

Skin and Nails

Psoriasis, a skin condition characterized by red, scaly patches on the skin, is often associated with psoriatic arthritis. In fact, up to 30% of people with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis. In addition to skin patches, psoriasis can also cause nail changes such as pitting, ridges, and discoloration.

Hands, Elbows, Feet, and Fingers

Psoriatic arthritis can affect any joint in the body, but it most commonly affects the joints of the hands, feet, and fingers. This can cause pain, swelling, and stiffness in these joints, making it difficult to perform daily activities.

Spine

Psoriatic arthritis can also affect the spine, causing pain and stiffness in the neck and lower back. This can make it difficult to bend, twist, or move the spine.

Eyes

Psoriatic arthritis can cause eye inflammation, a condition known as uveitis. Uveitis can cause eye redness, pain, and sensitivity to light. It is important to seek medical attention if you experience any of these symptoms.

Lungs

In rare cases, psoriatic arthritis can cause inflammation in the lungs, leading to shortness of breath and chest pain. This is known as psoriatic arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease.

Toes

Psoriatic arthritis can also affect the toes, causing pain and swelling in the joints of the toes. This can make it difficult to walk or wear shoes.

In conclusion, psoriatic arthritis can affect various body parts, causing a range of symptoms. It is important to seek medical attention if you experience any of these symptoms to receive an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Treatment and Management

When it comes to psoriatic arthritis of the knees, treatment and management are essential for reducing pain and inflammation, preventing joint damage, and improving overall quality of life.

There are several treatment options available, including medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, corticosteroid injections, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) like methotrexate, and biologics. The type of medication prescribed will depend on the severity of the disease and the patient’s overall health.

In addition to medication, managing pain and inflammation can be achieved through physical therapy, exercise, and lifestyle changes such as maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding triggers that worsen symptoms. Surgery may also be an option in severe cases where joint damage is significant.

It’s important to note that while there is no cure for psoriatic arthritis, achieving remission is possible with the right treatment plan. Regular checkups with a healthcare provider can help monitor the disease and adjust treatment as needed.

Overall, by working closely with healthcare providers and following a comprehensive treatment plan, individuals with psoriatic arthritis of the knees can effectively manage symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Living with Psoriatic Arthritis

Living with psoriatic arthritis can be challenging, but there are ways to manage symptoms and improve quality of life. We have compiled some tips and strategies to help those with psoriatic arthritis.

Exercise

Exercise is important for maintaining joint flexibility, muscle strength, and overall health. Low-impact exercises such as swimming, cycling, and yoga can be beneficial for those with psoriatic arthritis. It is important to consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new exercise program.

Damage

Psoriatic arthritis can cause joint damage if left untreated. It is important to work with a healthcare provider to develop a treatment plan to manage symptoms and prevent joint damage.

Diarrhea

Some medications used to treat psoriatic arthritis can cause diarrhea. It is important to discuss any side effects with a healthcare provider and to follow their recommendations for managing symptoms.

Heart

Psoriatic arthritis has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease. It is important to manage cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking.

Skin Cells and Plaques

Psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune skin disorder that causes skin cells to build up and form plaques. Psoriatic arthritis is a type of inflammatory arthritis that develops in people who have psoriasis. It is important to manage symptoms of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis to prevent joint damage and other complications.

Depression

Living with a chronic condition such as psoriatic arthritis can be difficult and can lead to depression. It is important to seek support from family, friends, and healthcare providers to manage symptoms of depression.

Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes

Psoriatic arthritis has been linked to an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and diabetes. It is important to manage these conditions with a healthy diet, regular exercise, and medication as prescribed by a healthcare provider.

Family Member

Psoriatic arthritis can run in families. It is important to inform family members of the condition and to encourage them to seek medical attention if they experience symptoms.

Healthcare Provider

Working with a healthcare provider is essential for managing psoriatic arthritis. It is important to communicate any symptoms or side effects of medication to a healthcare provider and to follow their recommendations for managing the condition.

Back Pain

Psoriatic arthritis can cause back pain and stiffness. It is important to work with a healthcare provider to develop a treatment plan to manage symptoms and prevent joint damage.

Bloating

Some medications used to treat psoriatic arthritis can cause bloating. It is important to discuss any side effects with a healthcare provider and to follow their recommendations for managing symptoms.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the early warning signs of psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis is a type of arthritis that affects some people who have psoriasis. The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis can vary, but some early warning signs include joint pain, stiffness, and swelling. Other common symptoms include fatigue, nail changes, and skin rashes. If you experience any of these symptoms, it is important to talk to your doctor.

What does psoriatic arthritis in knees feel like?

Psoriatic arthritis in knees can cause pain, swelling, and stiffness in the joints. This can make it difficult to walk, climb stairs, or stand for long periods of time. Some people with psoriatic arthritis in knees may also experience redness and warmth in the affected joint.

Does psoriatic arthritis hurt all the time?

No, psoriatic arthritis does not always hurt all the time. Some people with psoriatic arthritis may experience periods of time when their symptoms are mild or absent, while others may have ongoing pain and discomfort. It is important to work with your doctor to find a treatment plan that works for you.

Is walking good for psoriatic arthritis?

Yes, walking can be good for psoriatic arthritis. Exercise can help improve joint flexibility, reduce pain and stiffness, and improve overall health and well-being. However, it is important to talk to your doctor before starting any exercise program to make sure it is safe for you.

What are some common treatments for psoriatic arthritis?

There are several treatments available for psoriatic arthritis, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and biologic therapies. Your doctor may also recommend physical therapy, occupational therapy, or other treatments depending on your symptoms and the severity of your condition.

What does a psoriatic arthritis flare feel like?

A psoriatic arthritis flare can cause sudden and severe joint pain, swelling, and stiffness. This can make it difficult to move or perform everyday tasks. Flares can last for several days or weeks and may be triggered by stress, illness, or other factors. If you experience a flare, it is important to talk to your doctor about adjusting your treatment plan.