Introduction

Osteoporosis, often called the “silent disease,” is a condition characterized by decreased bone density and deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased fragility and risk of fractures. The condition affects approximately 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men over the age of 50, making it a significant public health concern worldwide. The impact of osteoporosis extends beyond bone health – hip fractures, in particular, are associated with a 3-4 times greater risk of dying within 12 months compared to the general population of the same age.

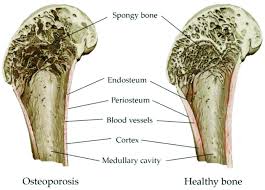

Throughout our lives, our bones undergo a continuous process of remodeling, with old bone being removed (resorption) and new bone being formed. In healthy individuals, this process maintains a balance. However, in osteoporosis, bone resorption outpaces bone formation, resulting in a net loss of bone mass and structural deterioration.

The good news is that osteoporosis is both preventable and treatable. While conventional medical treatments play a crucial role in managing the disease, especially for those at high fracture risk, natural approaches can complement these treatments and provide additional benefits for bone health. This article explores the full spectrum of osteoporosis management, from medical interventions to evidence-based natural therapies that can help strengthen bones and reduce fracture risk.

By understanding both conventional treatments and natural approaches, individuals can work with their healthcare providers to develop a comprehensive strategy tailored to their specific needs and risk factors.

Understanding Osteoporosis

To effectively address osteoporosis, it’s important to understand the disease process and the factors that contribute to its development. At its core, osteoporosis occurs when the body loses too much bone, makes too little bone, or both. This results in weakened bones that can break from minor falls or, in serious cases, even from simple actions like sneezing or bumping into furniture.

Several risk factors contribute to the development of osteoporosis:

- Age and Gender: Risk increases with age, with women at significantly higher risk than men. The rapid bone loss that occurs in the 5-7 years following menopause makes women particularly vulnerable.

- Genetic Factors: Family history of osteoporosis increases risk, as does being of Caucasian or Asian descent.

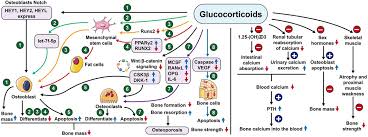

- Hormonal Changes: The decline in estrogen during menopause in women and testosterone in men accelerates bone loss. Other hormonal disorders, such as hyperthyroidism or hyperparathyroidism, can also affect bone health.

- Body Size: Small-framed individuals and those with low body weight have less bone mass to draw from as they age.

- Lifestyle Factors: Inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption all contribute to bone loss.

- Medications: Long-term use of certain medications, including corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, and some cancer treatments, can adversely affect bone health.

Osteoporosis is typically categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary osteoporosis is related to aging and hormonal changes, while secondary osteoporosis results from specific medical conditions or medications that affect bone metabolism.

Diagnosis typically involves dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA scan), which measures bone mineral density (BMD). The results are presented as a T-score, comparing an individual’s bone density to that of a healthy 30-year-old of the same sex. A T-score of -1.0 or above is considered normal, while scores between -1.0 and -2.5 indicate osteopenia (low bone mass), and scores below -2.5 indicate osteoporosis.

The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) may also be used to predict the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture based on individual risk factors, with or without BMD measurements.

One of the challenges of osteoporosis is that it progresses silently, often without symptoms until a fracture occurs. This makes screening and preventive measures crucial, especially for those with known risk factors.

Conventional Medical Treatments

Modern medicine offers several effective treatments for osteoporosis, designed to reduce fracture risk by slowing bone loss, increasing bone formation, or both. Treatment recommendations typically consider factors such as age, sex, fracture history, bone density measurements, and overall fracture risk.

First-Line Medications

Bisphosphonates remain the most commonly prescribed first-line treatment for osteoporosis. These medications slow bone resorption by inhibiting the activity of osteoclasts, the cells responsible for breaking down bone. The American College of Physicians (ACP) recommends bisphosphonates as the initial pharmacologic treatment for reducing fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Common bisphosphonates include:

- Alendronate (Fosamax) – taken weekly or monthly

- Risedronate (Actonel) – taken weekly or monthly

- Ibandronate (Boniva) – taken monthly or as quarterly injections

- Zoledronic acid (Reclast) – administered as a yearly intravenous infusion

These medications have been shown to reduce the risk of vertebral fractures by 40-70% and non-vertebral fractures, including hip fractures, by 20-40%. Side effects can include gastrointestinal issues with oral formulations and flu-like symptoms with intravenous formulations. Rare but serious side effects include osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fractures, particularly with long-term use.

Second-Line Treatments

When bisphosphonates are not appropriate or effective, several second-line treatments are available:

Denosumab (Prolia) is a RANK ligand inhibitor that blocks the development and activity of osteoclasts. Given as a subcutaneous injection every six months, it has been shown to reduce vertebral, non-vertebral, and hip fractures. Unlike bisphosphonates, denosumab does not accumulate in the bone, so its effects reverse quickly if treatment is stopped, potentially leading to rapid bone loss and increased fracture risk if not properly managed.

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) such as raloxifene (Evista) mimic estrogen’s beneficial effects on bone without some of the risks associated with estrogen. They can reduce vertebral fracture risk but have not been shown to reduce non-vertebral or hip fracture risk.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) was once widely used for osteoporosis prevention but is now primarily recommended for managing menopausal symptoms in women at high risk for osteoporosis, and only for the shortest duration possible due to potential risks of breast cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

Advanced Treatments for Severe Cases

For patients with severe osteoporosis or those who have experienced fractures despite other treatments, more potent options are available:

Anabolic Therapies stimulate bone formation rather than simply slowing bone loss. These include:

- Teriparatide and abaloparatide – synthetic forms of parathyroid hormone that stimulate bone formation when given intermittently. They are administered as daily injections for up to two years.

- Romosozumab (Evenity) – a sclerostin inhibitor that both increases bone formation and decreases bone resorption. It is given as monthly injections for one year.

These medications can increase bone density more substantially than antiresorptive drugs, especially at the spine. However, they are typically reserved for those at very high fracture risk due to their cost, route of administration, and limited treatment duration.

Treatment Duration and Management

The optimal duration of osteoporosis treatment continues to be studied. Many experts recommend reassessing after 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy, with consideration of a “drug holiday” for patients whose fracture risk has decreased. For high-risk patients, sequential therapy (starting with an anabolic agent followed by an antiresorptive) may provide optimal fracture protection.

Regular monitoring of bone mineral density and, in some cases, biochemical markers of bone turnover, can help assess treatment response and guide decisions about continuing or modifying therapy.

It’s important to remember that medication is just one component of osteoporosis management. All treatment approaches should be accompanied by adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, appropriate exercise, and measures to prevent falls.

Natural Therapy #1: Nutrition for Bone Health

Nutrition plays a fundamental role in both preventing and managing osteoporosis. While medications can effectively slow bone loss or stimulate bone formation, they cannot compensate for nutritional deficiencies that compromise bone health. A bone-healthy diet provides the essential building blocks needed for optimal bone remodeling and maintenance.

Calcium: The Foundation of Bone Health

Calcium is the primary mineral found in bone, making adequate intake essential throughout life. The recommended daily intake varies by age and gender:

- Adults aged 19-50: 1,000 mg

- Women aged 51+: 1,200 mg

- Men aged 51-70: 1,000 mg

- Men aged 71+: 1,200 mg

Dietary sources of calcium include:

- Dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese)

- Fortified non-dairy alternatives (soy milk, almond milk)

- Leafy green vegetables (kale, collard greens, bok choy)

- Calcium-set tofu

- Canned fish with bones (sardines, salmon)

- Fortified cereals and juices

While food sources are preferred, calcium supplements can help bridge dietary gaps. Two main types are available:

- Calcium carbonate: Higher concentration of elemental calcium (40%), best absorbed with food

- Calcium citrate: Lower concentration (21%), but better absorbed on an empty stomach and by those with reduced stomach acid

For optimal absorption, calcium supplements should be taken in doses of 500-600 mg or less at a time, spaced throughout the day. Taking them with meals can reduce the risk of kidney stones and improve absorption, particularly for calcium carbonate.

Vitamin D: The Essential Partner

Vitamin D is crucial for calcium absorption and proper bone mineralization. Without adequate vitamin D, the body cannot effectively utilize calcium, regardless of intake. Current recommendations include:

- Adults up to age 70: 600-800 IU daily

- Adults over 70: 800-1,000 IU daily

- Higher doses may be needed for those with vitamin D deficiency or limited sun exposure

Vitamin D sources include:

- Sunlight (the body produces vitamin D when skin is exposed to UVB rays)

- Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, tuna)

- Fortified foods (milk, orange juice, cereals)

- Egg yolks

- Supplements (D3 is generally preferred over D2)

Many healthcare providers recommend checking vitamin D levels through a blood test (25-hydroxyvitamin D) to determine if supplementation is needed. Optimal levels are generally considered to be 30-60 ng/mL.

Beyond Calcium and Vitamin D

While calcium and vitamin D receive the most attention, other nutrients also contribute to bone health:

- Protein: Provides the structural matrix for bone and stimulates insulin-like growth factor I, which promotes bone formation. Aim for 0.8-1.0 g/kg of body weight daily, from both animal and plant sources.

- Vitamin K: Important for bone protein synthesis. Found in leafy greens, broccoli, and fermented foods.

- Magnesium: Influences crystal formation in bone and calcium metabolism. Found in nuts, seeds, whole grains, and leafy greens.

- Potassium: Helps maintain acid-base balance, reducing calcium loss from bone. Abundant in fruits and vegetables.

- Zinc and Manganese: Essential for bone formation enzymes. Found in whole grains, nuts, and seeds.

Certain dietary patterns may also impact bone health. The Mediterranean diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, olive oil, and nuts, has been associated with higher bone density and lower fracture risk.

Conversely, some dietary factors may negatively affect bone health:

- High sodium intake increases calcium excretion

- Excessive caffeine may interfere with calcium absorption

- Very high protein diets can increase calcium excretion

- Carbonated beverages, particularly colas, have been associated with lower bone density in some studies

Natural Therapy #2: Exercise for Osteoporosis

Exercise is a powerful tool for building and maintaining bone strength. Unlike medication, which primarily works to slow bone loss, appropriate physical activity can actually stimulate bone formation, improve balance and coordination (reducing fall risk), and enhance overall functional capacity.

How Exercise Strengthens Bones

Bones respond to mechanical loading much like muscles respond to resistance – they adapt and strengthen. This phenomenon, known as Wolff’s Law, explains why weight-bearing activities and resistance training are particularly beneficial for bone health. When muscles pull on bones during these activities, they create stress that stimulates osteoblasts (bone-building cells) to lay down new bone tissue.

Different types of exercise affect bone health in different ways:

Weight-Bearing Exercises

Weight-bearing exercises force you to work against gravity while staying upright. These activities are particularly effective for strengthening the bones of the hips, legs, and lower spine. They include:

- High-impact weight-bearing exercises: Running, jumping, high-impact aerobics, dancing, tennis, and basketball can build bone mass effectively in those without osteoporosis or previous fractures.

- Low-impact weight-bearing exercises: Walking, elliptical training, stair climbing, and low-impact aerobics provide less bone stimulation but are safer options for those with osteoporosis, previous fractures, or other health limitations.

A general recommendation is to engage in weight-bearing aerobic activities for 30 minutes on most days of the week.

Resistance Training

Resistance or strength training involves working against resistance, whether from weights, bands, water, or body weight. These exercises target specific muscle groups and the bones they attach to. Effective resistance training for bone health includes:

- Free weights (dumbbells, barbells)

- Weight machines

- Resistance bands

- Body weight exercises (push-ups, squats)

Resistance training should be performed 2-3 times per week, targeting all major muscle groups. For bone health benefits, moderate intensity (8-12 repetitions with a weight that creates fatigue by the final repetition) is generally recommended.

Balance and Posture Exercises

While these exercises don’t directly build bone, they help prevent falls – a critical consideration for those with osteoporosis:

- Tai chi

- Yoga (with modifications for osteoporosis)

- Posture training

- Stability ball exercises

- Single-leg standing

Balance exercises should be incorporated into daily routines, even if just for a few minutes each day.

Exercise Precautions for Osteoporosis

For those already diagnosed with osteoporosis, exercise remains beneficial but requires certain precautions:

- Avoid high-impact activities if you have severe osteoporosis or previous fractures

- Avoid rapid, forceful movements that might increase fracture risk

- Avoid extreme forward bending and twisting of the spine

- Focus on proper form rather than amount of weight lifted

- Start slowly and progress gradually

- Consider working with a physical therapist to develop a safe, effective program

Developing an Exercise Program

An ideal exercise program for bone health includes:

- 30 minutes of weight-bearing aerobic activity on most days

- Resistance training for all major muscle groups 2-3 times weekly

- Balance exercises daily

- Posture and core strengthening exercises regularly

For those new to exercise or with health concerns, starting with a physical therapist or qualified fitness professional experienced in working with osteoporosis is recommended. They can design a program tailored to individual needs, limitations, and goals.

Remember that consistency is key – the bone benefits of exercise are lost when activity stops, so finding enjoyable activities that can be maintained long-term is essential for ongoing bone health.

Natural Therapy #3: Vitamin K for Bone Health

Vitamin K has emerged as an important nutrient for bone health that often doesn’t receive the same attention as calcium and vitamin D. Research increasingly suggests that adequate vitamin K intake is essential for optimal bone metabolism and strength.

The Role of Vitamin K in Bone Metabolism

Vitamin K serves as a cofactor for the enzyme that activates osteocalcin, a protein that binds calcium to the bone matrix. Without sufficient vitamin K, osteocalcin remains inactive, leading to reduced bone mineralization and potentially increased fracture risk.

There are two main forms of vitamin K:

- Vitamin K1 (Phylloquinone): The primary dietary form, found mainly in green leafy vegetables

- Vitamin K2 (Menaquinones): Found in fermented foods and produced by intestinal bacteria; appears to be more effective for bone health than K1

Studies have found that higher vitamin K intake is associated with higher bone mineral density and lower fracture risk. Low circulating levels of vitamin K have been linked to lower bone mass and increased fracture risk, particularly hip fractures.

Dietary Sources of Vitamin K

The best food sources of vitamin K include:

- Vitamin K1 sources: Kale, spinach, collard greens, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, lettuce

- Vitamin K2 sources: Natto (fermented soybeans), cheese, egg yolks, butter from grass-fed cows, fermented foods

The adequate intake (AI) for vitamin K is:

- Adult women: 90 micrograms per day

- Adult men: 120 micrograms per day

However, optimal amounts for bone health may be higher than these basic recommendations.

Vitamin K Supplementation

Research on vitamin K supplementation for osteoporosis has shown mixed results. Some studies, particularly those using vitamin K2 (MK-4 form) at doses of 45mg daily, have shown reduced fracture risk in Japanese populations. Other studies using different forms or lower doses have shown more modest or inconsistent effects.

When considering vitamin K supplementation:

- Form matters: Vitamin K2, particularly the MK-4 and MK-7 forms, may be more beneficial for bone health than K1

- Dosage varies: Therapeutic doses used in studies range from 45-180 micrograms for MK-7 and up to 45mg for MK-4

- Medication interactions: Vitamin K can interfere with certain blood-thinning medications, particularly warfarin. Those taking such medications should consult their healthcare provider before supplementing

Current Evidence and Recommendations

While the evidence for vitamin K supplementation is promising, it’s not yet conclusive enough for most major medical organizations to recommend routine supplementation specifically for osteoporosis. Current approaches include:

- Ensuring adequate vitamin K intake through diet, particularly green leafy vegetables

- Considering supplementation under healthcare provider guidance, especially for those with low dietary intake or at high fracture risk

- Using vitamin K as part of a comprehensive bone health strategy that includes calcium, vitamin D, and other nutrients

For those interested in supplementation, consulting with a healthcare provider is essential, particularly for those on medications that might interact with vitamin K.

Natural Therapy #4: Magnesium and Bone Health

Magnesium is an essential mineral that plays multiple roles in bone health yet is often overlooked in discussions about osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Approximately 60% of the body’s magnesium is stored in bone tissue, highlighting its importance to skeletal structure.

Magnesium’s Role in Bone Metabolism

Magnesium contributes to bone health through several mechanisms:

- It influences the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, the cells responsible for bone formation and resorption

- It affects crystal formation in bone, influencing bone quality and strength

- It regulates calcium transport and metabolism

- It is required for the conversion of vitamin D to its active form, which is necessary for calcium absorption

- It helps maintain appropriate calcium levels in the blood and tissues

Research has found that magnesium deficiency is associated with reduced bone mineral density, altered bone and mineral metabolism, and increased fracture risk. One study found that 40% of women with osteoporosis or low bone density had low circulating magnesium levels.

Dietary Sources of Magnesium

The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for magnesium is:

- Adult women ages 19-30: 310 mg daily

- Adult women ages 31+: 320 mg daily

- Adult men ages 19-30: 400 mg daily

- Adult men ages 31+: 420 mg daily

Excellent food sources of magnesium include:

- Dark leafy greens (spinach, chard)

- Nuts and seeds (almonds, pumpkin seeds)

- Whole grains (brown rice, quinoa)

- Legumes (black beans, chickpeas)

- Dark chocolate

- Avocados

- Bananas

Despite its abundance in whole foods, many people don’t consume enough magnesium due to dietary patterns high in processed foods, which typically contain little magnesium. Soil depletion of minerals may also reduce the magnesium content of foods compared to historical levels.

Magnesium Supplementation

For those who cannot meet their magnesium needs through diet alone, supplements can be beneficial. Several forms are available, each with different properties:

- Magnesium citrate: Well-absorbed, may have a mild laxative effect

- Magnesium glycinate: Well-absorbed with minimal digestive side effects

- Magnesium malate: Well-tolerated and may help with muscle pain

- Magnesium oxide: Lower absorption rate but higher elemental magnesium content

- Magnesium chloride: Good absorption and often available as a topical oil

When supplementing, it’s generally recommended to start with a lower dose and gradually increase to avoid digestive discomfort. Taking magnesium supplements with food can also improve tolerance.

Safety Considerations

While magnesium is generally safe, excessive intake from supplements (not food) can cause diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal cramping. In people with reduced kidney function, high doses of magnesium supplements can lead to magnesium toxicity, characterized by low blood pressure, confusion, and cardiac complications.

Those with kidney disease, heart problems, or on certain medications should consult their healthcare provider before supplementing with magnesium.

Evidence and Recommendations

While more research is needed on the specific effects of magnesium supplementation on fracture risk, ensuring adequate magnesium intake is a sensible strategy for supporting bone health. The greatest benefits are likely to be seen in those who are magnesium deficient.

Current recommendations include:

- Prioritizing magnesium-rich whole foods in the diet

- Considering supplementation if dietary intake is insufficient or if deficiency is suspected

- Integrating magnesium into a comprehensive bone health approach alongside calcium, vitamin D, and other supportive nutrients

Natural Therapy #5: Soy Isoflavones and Phytoestrogens

The dramatic increase in osteoporosis risk that follows menopause highlights the crucial role of estrogen in maintaining bone health. As estrogen levels decline, bone resorption accelerates, often leading to significant bone loss in the first 5-7 years after menopause. This connection between estrogen and bone health has led researchers to investigate plant compounds with estrogen-like properties, known as phytoestrogens, as potential natural therapies for osteoporosis.

Understanding Isoflavones and Phytoestrogens

Isoflavones are a class of phytoestrogens – plant compounds that have a structure similar to human estrogen and can bind to estrogen receptors in the body, though their effects are typically much weaker than those of human estrogen. The most well-studied isoflavones include:

- Genistein

- Daidzein

- Glycitein

These compounds are found primarily in soybeans and soy products, but also in smaller amounts in other legumes such as chickpeas, lentils, and beans.

Mechanisms of Action

Isoflavones may support bone health through several mechanisms:

- Binding to estrogen receptors in bone tissue, potentially slowing bone resorption

- Inhibiting the activity of osteoclasts (cells that break down bone)

- Supporting the activity of osteoblasts (cells that build bone)

- Providing antioxidant effects that may protect bone cells from oxidative stress

Research on Isoflavones and Bone Health

Research on soy isoflavones for bone health has shown promising but mixed results:

A meta-analysis of 19 studies in postmenopausal women found that soy isoflavone supplementation significantly increased bone mineral density by 54% and reduced bone resorption markers by 23% compared to baseline values. The most significant benefits were seen in studies lasting at least one year and using higher doses (80-90 mg of isoflavones daily).

However, not all studies have shown positive results, and the effects may vary based on factors such as:

- Individual metabolism of isoflavones (some people convert daidzein to equol, a more potent compound, while others do not)

- Age and years since menopause

- Baseline bone density

- Dose and type of isoflavones used

- Study duration

Dietary Sources of Isoflavones

The richest food sources of isoflavones include:

- Soybeans and whole soy foods (tofu, tempeh, edamame)

- Soy flour and soy protein

- Soy milk and other soy beverages

- Other legumes (chickpeas, lentils, beans)

- Red clover (used in some supplements)

The isoflavone content varies widely among soy foods, with whole and minimally processed soy foods generally providing higher amounts than highly processed soy ingredients.

Supplementation Considerations

For those considering isoflavone supplements for bone health:

- Dosage: Studies showing benefits typically used 40-110 mg of isoflavones daily

- Duration: Longer-term use (at least one year) appears necessary for significant effects on bone

- Form: Supplements may contain isolated isoflavones or whole soy extracts

- Quality: Look for standardized products from reputable manufacturers

Safety and Concerns

While moderate consumption of dietary soy is generally considered safe for most people, questions have been raised about the long-term safety of isolated isoflavone supplements, particularly for women with a history of hormone-sensitive conditions such as breast cancer.

Current evidence does not indicate that moderate soy consumption increases breast cancer risk, and some studies suggest it may even be protective. However, the effects of high-dose isoflavone supplements taken for extended periods are less well understood.

Potential side effects of isoflavone supplements may include:

- Digestive discomfort

- Menstrual changes in premenopausal women

- Theoretical interactions with thyroid hormones

Recommendations for Use

Given the current evidence:

- Including whole soy foods in the diet is a reasonable approach for supporting bone health

- Those considering supplements should discuss them with their healthcare provider

- Women with a history of hormone-sensitive conditions should be particularly cautious and seek medical guidance

- Isoflavones should be viewed as one component of a comprehensive bone health program, not as a standalone treatment for osteoporosis

As research continues, our understanding of the optimal use of isoflavones for bone health will likely evolve.

Natural Therapy #6: Lifestyle Modifications

Beyond nutrition and targeted supplements, several lifestyle modifications can significantly impact bone health and fracture risk. These changes, while sometimes overlooked, can be powerful components of a comprehensive approach to osteoporosis prevention and management.

Smoking Cessation

Smoking has multiple detrimental effects on bone health:

- It reduces blood supply to bones

- It impairs the function of osteoblasts (bone-building cells)

- It interferes with calcium absorption

- It alters hormonal balance, including estrogen levels

- It may accelerate the breakdown of exogenous estrogen

Studies have consistently shown that smokers have lower bone density and higher fracture risk compared to non-smokers. The longer one smokes, the greater the impact on bone health.

The good news is that quitting smoking can help slow the rate of bone loss, though it may not fully reverse existing damage. Former smokers gradually see their fracture risk decrease after quitting, though it may take years to approach the risk level of people who never smoked.

Resources for quitting smoking include nicotine replacement therapies, prescription medications, counseling programs, and support groups. Healthcare providers can help develop a personalized smoking cessation plan.

Alcohol Moderation

Excessive alcohol consumption negatively impacts bone health through multiple mechanisms:

- Direct toxic effects on osteoblasts

- Interference with vitamin D metabolism and calcium absorption

- Disruption of hormone production and metabolism

- Increased fall risk

- Malnutrition associated with heavy drinking

Moderate alcohol consumption (up to one drink daily for women and up to two drinks daily for men) has not been clearly associated with increased osteoporosis risk. However, heavy drinking significantly increases the risk of bone loss and fractures.

For those who drink heavily, reducing alcohol consumption or abstaining completely can help preserve bone mass and reduce fracture risk. Support is available through healthcare providers, counseling, and programs like Alcoholics Anonymous.

Fall Prevention Strategies

For those with osteoporosis, preventing falls is crucial for avoiding fractures. Comprehensive fall prevention includes:

Home Safety Modifications:

- Remove tripping hazards (loose rugs, clutter)

- Improve lighting, especially in stairways and at night

- Install grab bars in bathrooms and on stairs

- Use non-slip mats in bathtubs and showers

- Consider placing frequently used items within easy reach

Personal Safety Measures:

- Wear properly fitting, supportive shoes with non-slip soles

- Use assistive devices (cane, walker) if needed

- Get up slowly from sitting or lying positions to avoid dizziness

- Use caution when walking on wet, icy, or uneven surfaces

- Consider wearing hip protectors if at very high fall risk

Health Management:

- Review medications with healthcare providers to identify those that might cause dizziness or affect balance

- Get regular vision and hearing checks

- Address foot problems promptly

- Manage conditions that might affect balance, such as Parkinson’s disease or arthritis

Stress Management

Emerging research suggests that chronic stress may contribute to bone loss through several mechanisms:

- Increased production of cortisol, which can directly inhibit bone formation

- Disruption of calcium absorption and metabolism

- Inflammation, which can accelerate bone resorption

- Indirect effects through poor diet, reduced physical activity, and increased smoking or alcohol consumption associated with stress

Effective stress management techniques include:

- Mindfulness meditation

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Regular physical activity

- Adequate sleep

- Social connection

- Cognitive-behavioral techniques

- Time in nature

Incorporating stress reduction into daily routines can support overall health, including bone health.

Weight Management

Maintaining a healthy weight is important for bone health:

- Being underweight (BMI < 18.5) is a significant risk factor for low bone density and fractures

- Very high body weight increases stress on bones and risk of falls

- Weight cycling (repeated weight loss and regain) may be detrimental to bone density

Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight through nutritious eating and regular physical activity supports optimal bone health and reduces fracture risk.

Integrating Conventional and Natural Approaches

The most effective approach to osteoporosis prevention and treatment often combines conventional medical treatments with natural therapies. This integrated strategy addresses the condition from multiple angles, potentially providing more comprehensive protection against bone loss and fractures than either approach alone.

Building a Comprehensive Treatment Plan

An optimal osteoporosis management plan typically includes:

- Proper medical assessment and diagnosis, including bone density testing, fracture risk assessment, and evaluation for secondary causes of osteoporosis

- Appropriate medication based on individual risk factors, with higher-risk individuals typically benefiting most from pharmacologic intervention

- Nutritional optimization with adequate calcium, vitamin D, protein, and other bone-supporting nutrients

- Regular weight-bearing and resistance exercise tailored to individual fitness level and fracture risk

- Targeted supplementation based on individual needs, potentially including vitamin K, magnesium, and isoflavones for appropriate candidates

- Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, alcohol moderation, and fall prevention strategies

- Regular monitoring of bone density, biochemical markers, and overall health status to assess progress and adjust the plan as needed

Personalizing Your Approach

The optimal combination of treatments varies based on individual factors:

- Age and gender: Younger individuals may focus more on prevention through nutrition and exercise, while those at higher risk due to age or menopause may need more aggressive intervention

- Fracture history and risk level: Those with previous fractures or very low bone density typically need medical treatment alongside natural approaches

- Personal preferences and values: Some individuals may prefer to emphasize lifestyle and nutritional approaches, while others may be more comfortable with medication

- Comorbidities: Other health conditions and medications may influence which treatments are most appropriate

- Response to treatment: The approach may need adjustment based on how bone density and other markers respond over time

Working with Healthcare Providers

Effective osteoporosis management requires collaboration with healthcare providers, potentially including:

- Primary care physician

- Endocrinologist or rheumatologist

- Registered dietitian

- Physical therapist

- Pharmacist

Open communication about all therapies being used, including supplements and exercise programs, is essential to avoid potential interactions and ensure complementary rather than conflicting approaches.

Potential Interactions to Consider

Some natural therapies may interact with osteoporosis medications or other treatments:

- Calcium supplements can interfere with the absorption of certain medications, including some antibiotics and thyroid medications, and should be taken at different times

- Vitamin K supplements can interfere with warfarin and other blood-thinning medications

- High-dose vitamin A supplements may counteract the beneficial effects of vitamin D and potentially harm bone health

- Some herbal supplements may interact with osteoporosis medications or affect bone metabolism through unknown mechanisms

Discussing all supplements with healthcare providers helps minimize the risk of adverse interactions.

Monitoring Progress

Regular assessment helps determine whether the treatment plan is working:

- Bone density testing typically every 1-2 years while establishing treatment efficacy, then potentially less frequently

- Blood and urine tests to assess bone turnover markers and vitamin D levels

- Height measurements to detect potential vertebral fractures

- Fall risk assessments

- Review of any pain or functional limitations

Based on these assessments, the treatment plan can be adjusted to optimize outcomes.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis is a complex condition that requires a multifaceted approach to prevention and treatment. While conventional medical treatments play a crucial role, especially for those at high fracture risk, natural therapies can significantly complement these approaches and provide additional benefits for bone health.

The six natural therapies discussed – nutrition, exercise, vitamin K, magnesium, soy isoflavones, and lifestyle modifications – each address different aspects of bone health. When combined appropriately and personalized to individual needs, they create a comprehensive strategy that supports both bone quantity (density) and quality (structure).

The most effective approach is typically one that integrates conventional and natural strategies based on individual risk factors, preferences, and needs. This may mean using medications for those at high fracture risk while simultaneously optimizing nutrition, incorporating appropriate exercise, and addressing lifestyle factors that affect bone health.

For those at lower risk, focusing primarily on natural approaches may be appropriate, with regular monitoring to ensure bone health is maintained. The key is early intervention – whether through natural or conventional means – as preventing bone loss is easier than reversing it once significant deterioration has occurred.

Working collaboratively with healthcare providers to develop and adjust your bone health strategy over time ensures that you receive the most appropriate combination of treatments for your specific situation. With this comprehensive approach, many individuals can maintain bone strength, reduce fracture risk, and continue to lead active, independent lives despite osteoporosis.

References

- American College of Physicians. (2023). Pharmacologic Treatment of Primary Osteoporosis or Low Bone Mass to Prevent Fractures in Adults: A Living Clinical Guideline.

- Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. (2024). Calcium/Vitamin D Requirements, Recommended Foods & Supplements.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. (2024). New evidence-based guideline for the management of osteoporosis in men.

- National Institutes of Health. (2021). Vitamin D Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. (2023). Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis.

- Palermo, A., et al. (2017). Vitamin K and osteoporosis: Myth or reality? Metabolism, 70, 57-71.

- Rodríguez-Olleros Rodríguez, C., & Díaz Curiel, M. (2019). Vitamin K and Bone Health. Journal of Osteoporosis.

- Taku, K., et al. (2010). Effect of soy isoflavone extract supplements on bone mineral density in menopausal women. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

- Watson, R.R., & Preedy, V.R. (2020). Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for the Aging Population.

- Weaver, C.M., et al. (2016). Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures. Osteoporosis International.

Leave a Reply