Overview

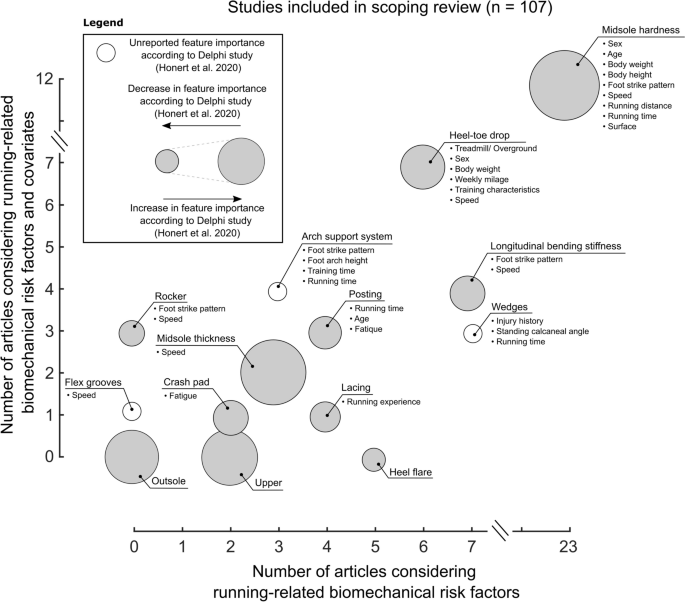

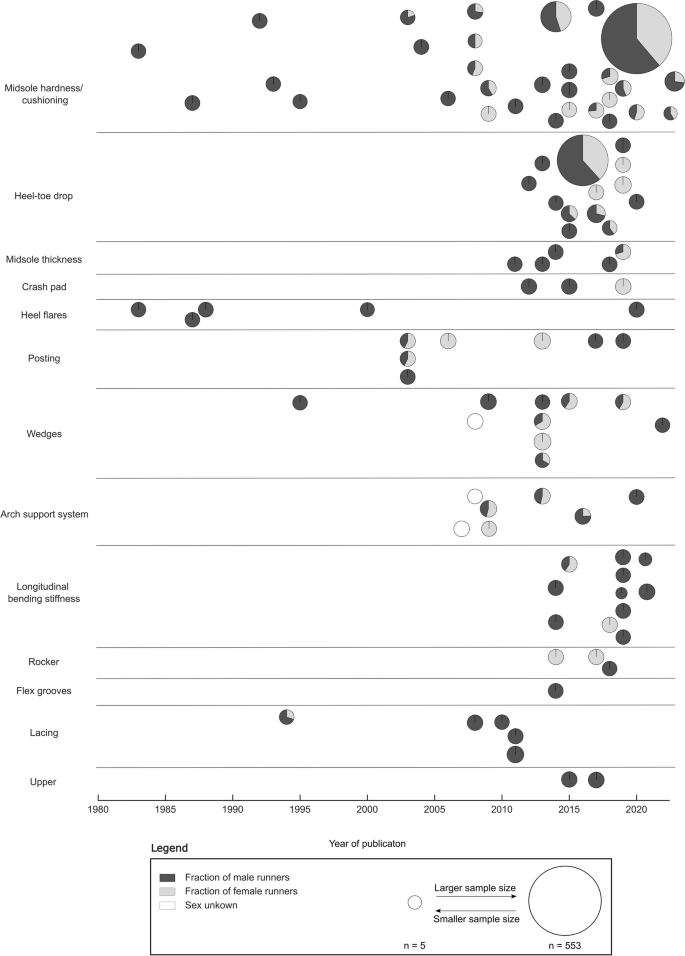

Running shoes are often characterised based on their cushioning and motion control functionality. Consequently, we have categorised the literature review results into these sections. We discuss additional FDF that did not fit into the first two sections in a subsequent part, followed by an upper construction segment. In each chapter, we introduce a brief description of the FDF. Next, we present the results of studies, taking covariates into account and analysing BRFs. We further discuss studies that investigated BRFs without considering covariates. Finally, we place our findings in the context of the FDF’s potential to minimise the development of running-related overuse injuries (RRI). We identified 107 articles that met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 4, Supplementary 3 Table 1-12). Most of these articles were published at the start of the twenty-first century and primarily featured data from male runners (Fig. 5). We acknowledge a data gap in running footwear research, which aligns with the female data gap in sport and exercise science [24].

Cushioning systems

Cushioned midsoles were one of the first FDF introduced to modern running shoes. They were developed to provide a protective layer, attenuate the shock caused by the collision of the foot with the ground, and reduce local plantar pressure peaks [26]. The cushioning characteristics are modified in the midsole through material and geometry changes.

Midsole compression stiffness and hardness

Midsole compression stiffness, also known as hardness, is a fundamental material property that measures the deformation caused by an area load. In the past, midsoles were constructed with uniformly distributed compression stiffness. However, they can now be tailored to individually cushioned midsoles with varying properties at different locations due to the viscoelastic properties of the material [27].

Twelve of thirty-five articles identified through our literature search considered covariates when analysing the response to differently cushioned midsoles (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 1). Malisoux et al. considered the runner’s body mass as a covariate [28]. Athletes reported fewer injuries when running in softer midsoles, and lighter runners in hard shoes showed a greater risk of developing an RRI than heavier runners. Three articles investigated the biomechanical response of midsoles with varying hardness during different running speeds. Nigg et al. found that the vertical GRF loading rate increases with speed independent of the cushioning variations, while another study showed unchanged GRF loading rates with footwear of varying cushioning at different speeds, and yet another study showed lower GRF loading rates in harder midsoles with no dependence on running speed [29,30,31]. Running distance or running duration has been considered by five studies [32,33,34,35,36]. None of the studies found significant footwear-by-time/distance interaction effects on vertical GRF loading rates, ground contact times, peak rearfoot eversion angles, and knee flexion angle at initial contact. One article considered the runner’s foot strike pattern as a covariate [37]. Rearfoot strikers reduced the vertical GRF loading rate in a neutrally cushioned shoe, and mid- and forefoot strikers reduced the vertical GRF loading rate in a minimal shoe [37]. We identified one study considering the stiffness of the running surface as a covariate [38]. However, no main and interaction effects were observed in ground contact time and knee flexion angle at touchdown. Another study analysed the effect of surface inclination and midsole cushioning [39]. The authors showed that vertical GRF loading rates are equal when running on different surfaces with either a neutral or a cushioned running shoe. Although studies have examined a variety of covariates, there is much conjecture in the literature regarding their influence on biomechanical measures related to RRI, and no conclusive evidence to suggest that any one covariate is more important than another.

When considering the effects of midsole hardness on BRFs without considering covariates, five studies found reduced peak rearfoot eversion in harder midsoles than in softer midsoles [40,41,42,43,44]. However, four studies found unchanged peak rearfoot eversion angles when running in soft and hard midsoles [34, 45,46,47]. Four studies reported that different midsole hardness could not systematically affect the rearfoot eversion range of motion [40, 44, 45, 48]. In contrast, one study found a reduction in the rearfoot eversion range of motion in hard midsoles [47], and another study found that the range of motion of the rearfoot was lower when runners were running in softer midsoles [49]. Conflicting findings were also observed for the rearfoot inversion angle at initial ground contact. One study found a reduction in rearfoot inversion when running in soft midsoles [40], and others found reduced inversion angles when running in hard midsoles [40, 48]. Conflicting findings have also been reported for the vertical GRF loading rate. Some studies found an increased vertical GRF loading rate in more cushioned than less cushioned shoes [29, 34]. Other studies found no effects of cushioning [46, 50,51,52], while others found decreased vertical GRF loading rate in cushioned shoes [41]. Only a few studies were identified addressing the effects of different cushioning characteristics on BRFs at more proximal joints. One article’s qualitative data showed that the knee abduction angle during the stance phase was reduced when running in softer than harder midsoles [53]. In contrast, another study found lower peak knee abduction angles when the midsole was manufactured with harder material [47]. A study by Malisoux and colleagues found that both soft and hard midsoles did not change peak hip abduction angles and moments and peak hip internal rotation angles [45]. When considering ground contact time as BRF for PFPS, most studies found no effect of midsole cushioning [29, 36, 38, 45, 49, 51, 54,55,56]. Overall, studies analyzing BRFs without considering covariates, resulted in inconsistent and conflicting findings. Interestingly, the footwear comfort perception reported by participants tends to be higher in regions where softer material is allocated than in those with harder materials [42, 49, 57, 58].

In summary, the current literature suggests that the midsole hardness can potentially reduce the overall injury risk when adjusted to the runner’s body mass. Reduction in vertical GRF loading rates and subsequent minimizing PF injury risk could be achieved by individualising midsole cushioning to the runner’s foot strike pattern. Specifically, rearfoot strikers might benefit from cushioned shoes, while fore- and midfoot strikers could find minimal shoes advantageous. The lower vertical GRF loading rates observed in neutral shoes compared to cushioned shoes when running downhill suggest that customised midsole cushioning tailored to a runner’s training terrain could benefit runners with a PF history. Based on the limited literature, surface stiffness, running distance, and fatigue might be less important when individualising midsole hardness. Harder midsoles can reduce BRFs associated with MTSS, TSF, AT (rearfoot eversion movement), and ITBS (ground contact times). Indications that different shoe cushioning may alter vertical GRF loading rates are contradictory, and BRFs at more proximal joints have not been well studied.

Midsole geometry

Running footwear is often designed with a height gradient from the heel to the forefoot. Running shoes are defined by their heel and forefoot heights, with the difference between the two known as the heel-toe drop. Unlike neutral or motion-control shoes, minimal footwear is typically designed with a lower heel-toe drop. An increase in footwear minimalism generally shifts the foot strike pattern of rearfoot strikers towards a mid- or forefoot strike pattern, and it is further assumed to reduce impact loading parameters [59, 60].

We identified eighteen articles investigating the effects of geometrical midsole modifications matching our inclusion criteria (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 2). Out of the eighteen articles, nine accounted for a covariate. The runner’s experience was considered in one article [61]. During a six-month follow-up, it was shown that occasional runners (< 6 months running experience) had reduced injury rates, and recreational runners (≥ 6 months running experience) had increased injury rates when running in footwear with lower heel-toe drop. A subset of this data demonstrated that midsoles with different heel-toe drops were not able to reduce peak rearfoot eversion angle and ground contact time [62]. However, runners who trained for six months in footwear with higher heel-toe drops increased the peak knee abduction angle. On the contrary, runners who trained for six months in footwear with lower heel-toe drops reduced the peak knee abduction angle. Running surface as a covariate was considered by one study [63]. The researchers found smaller knee flexion angles for larger heel-toe drops when running on a treadmill. However, when running overground, the knee flexion angle was not changed when running in shoes with different heel-toe drops. The authors found that increasing the heel-toe drop led to lower vertical GRF loading rates overground, but decreasing the heel-toe drop reduced vertical GRF loading rates during treadmill running. Different running speeds as a covariate were considered by four articles [64,65,66,67]. One study found no changes in the knee flexion angle at initial contact when running at different speeds in midsoles with different heel-toe drop designs [64]. Another study showed that while ground contact time decreased with increasing speed, increasing the heel-toe drop resulted in increased contact time [65]. Other researchers also showed similar results when systematically altering running speed and heel-toe drop [66]. Running speed did not influence the effects of heel-toe drop modifications on vertical GRF loading rates or time spent in rearfoot eversion [67]. The interaction effects of running time and geometrical midsole modifications were investigated in two studies using the same data set [68, 69]. However, neither of the studies reported interaction effects on included BRFs (rearfoot movement, contact time, and knee flexion angle at initial ground contact). Nevertheless, both studies reported longer ground contact times, lower rearfoot eversion range of motion, and greater knee flexion angles at initial contact in thicker than thinner midsoles.

Concerning the general effects of midsole geometries on BRFs without considering covariates, most of the included studies have addressed the effect of midsole geometry on GRF parameters. An increase in heel-toe drop has been reported to reduce vertical GRF loading rates [70,71,72,73]. Diverse results have been reported for midsole thickness, for which one study found lower vertical GRF loading rates in thicker than thinner midsoles [74], whereas another study could not identify any differences [75]. Three studies showed that geometrical changes at the midsole do not affect rearfoot inversion at touchdown [68,69,70]. Three articles showed that the knee flexion angle at touchdown remains unchanged independent of geometrical midsole configurations [72, 75, 76]. Only one study collected comfort perception data from fifteen male runners [77]. However, no difference in comfort was observed when the heel-toe drop was systematically altered.

Summarising the results, individualisation of heel-toe drop based on runner experience may reduce the risk of RRI. Although the underlying biomechanical mechanism remains unknown, a gradual transition from shoes with different heel-to-toe drops may allow adequate adaptation of the biological tissues. Running surfaces can affect the response to heel-toe drop alterations by influencing vertical GRF loading rates and knee flexion angles. Runners with a history of PF training on treadmills may benefit from shoes with a lower heel-toe drop, while those with a history of ITBS may benefit from a higher drop. During fatigue, geometric midsole modifications may not affect rearfoot eversion movement or ground contact times. Thinner midsoles with a lower heel-toe drop may reduce ground contact times, peak rearfoot eversion angle and rearfoot eversion duration. Hence, these modifications might be recommended for runners with a risk or a history of PFPS, TSF, or MTSS. Moreover, thicker midsoles with a higher heel-toe drop might shift BRFs related to AT and PF (rearfoot eversion range of motion and vertical GRF loading rate) to potentially less critical BRF magnitudes.

Motion control features

Motion control, also called stability, in footwear refers to how the shoe limits pronation (calcaneal eversion) or supination (calcaneal inversion) during the support phase. Much research has been devoted to FDF that purports to control pronation or eversion motion, motivated by the retrospective observations that increased pronation angle is associated with RRI [10, 78,79,80]. Over the initial period of footwear research, various midsole technologies were designed to increase rearfoot stability, including altering the midsole hardness, location of material inserts, flares, arch support systems, and postings. One of the few identified studies utilized a randomized controlled trial with a six-month follow-up. The findings revealed that recreational runners with a motion control shoe developed fewer RRI than runners receiving a standard running shoe [15]. Interestingly, motion-control shoes’ effectiveness in reducing RRI development was more pronounced for runners with pronated feet, indicating some potential for footwear individualisation.

Postings

Postings in athletic footwear incorporate elements with higher material densities in the medial rearfoot region and have been reported to limit rearfoot eversion [81]. Unlike wedges, postings are designed without gradual height differences [82].

Three of seven articles identified through our literature search considered covariates in their analysis (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3). The runner’s age was considered by one article [83]. Medial posts effectively reduced the amount of rearfoot eversion in older compared to younger female runners, while vertical GRF loading rates, peak knee abduction moments, and peak knee internal rotation angles remained unchanged. When considering the runners’ fatigue as a covariate, two articles found that rearfoot eversion movement (peak and range of motion) was lower when running in a medially posted than in a neutral running shoe when the runner’s fatigue increased [84, 85].

When not considering covariates or subgroups of runners, medial postings can reduce peak rearfoot eversion angles and eversion range of motion [86, 87]. Peak knee internal rotation angles are reported to be reduced when running in footwear with medial postings [83, 88]. However, footwear with postings might increase peak hip abduction moments [89]. Diverse results were found for vertical GRF loading rates. One study found lower vertical GRF loading rates in midsoles without medial posts [87], and another found unchanged vertical GRF loading rates in shoes with and without postings [83]. Some runners have perceived the harder posting material without transitions as uncomfortable, potentially resulting in unwanted changes in their biomechanics [88].

In summary, older female runners with a history of TSF and MTSS might reduce rearfoot eversion in shoes with postings. However, medial posts do not seem to affect the risk of developing PF independent of the runners’ age since changes in vertical GRF loading rates were not observable. Based on the limited literature, posted midsoles may help minimise BRFs (rearfoot eversion movement) associated with AT, MTSS, or TSF as the runners’ fatigue state increases. The limited literature suggests that individualised postings can help runners with a history of AT, MTSS, TSF, or ITBS to reduce biomechanical risk factors. Since postings might increase vertical GRF loading rates, caution needs to be taken by runners with a history of PF.

Wedges

Wedges are sloped orthotic inserts, typically with mediolateral elevation, designed to increase foot stability. Mediolateral elevation under different loading conditions can be achieved by incorporating materials with different mechanical properties at distinguished locations of the wedge [90].

Three out of the ten articles identified in the literature search included a covariate in their analysis (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 4). One study considered running duration (0–30 min) as a covariate [91]. Independent of the running duration, medially wedged insoles produced lower knee abduction angular impulses than laterally wedged insoles. Another study considered different standing calcaneal angles and injury history as covariates [92]. However, wearing differently wedged insoles showed no effect on female runners’ 3D knee and hip kinematics. Anterior knee pain as a covariate and the response to differently wedged insoles were considered by one article [93]. Independent of knee pain, running in medially wedged insoles reduced maximal rearfoot eversion and range of motion compared to running in footwear without wedges. None of the studies personalised the wedges to the runner’s individual foot anatomy; instead, they used pre-fabricated wedges, which may have confounded these results.

Seven articles were identified investigating the effect of wedged insoles on BRFs without considering covariates. In a study in which the wedges were customised to individual dynamic barefoot plantar pressure data, all but two subjects reduced peak rearfoot eversion angles compared to footwear without wedges [94]. This finding suggests that wedges bear high potential when individualised to foot pressure mapping. Pre-fabricated medial wedges have proven effective in decreasing maximal rearfoot eversion angles and eversion range of motion [94,95,96,97]. When comparing footwear with and without wedges, non-systematic changes in vertical GRF loading rates and knee abduction angular impulse have been reported [95, 96, 98, 94, 99, 100]. When the mediolateral elevation was systematically altered, no perceived comfort and stability changes were reported [95]. Moreover, neither medially nor laterally wedged insoles were able to relieve runners of patellofemoral pain [99]. One study introduced forefoot wedges with systematic changes in elevation; however, no changes in ground contact times were reported [101].

In summary, the response to medially wedged insoles is independent for shorter running durations (< 30 min) but may help runners with a history of PFPS to minimise knee abduction angular impulses; however, the effect for longer running durations (> 30 min) remains unknown. The limited literature shows that joint alignments, injury history, and knee pain are less relevant covariates when individualising wedged insoles. Medially wedged insoles might sufficiently limit rearfoot eversion movement and support runners with a history of AT, TSF, and MTSS to reduce reinjury. To attenuate vertical GRF loading rates, runners with a history of PF might refer to other FDF modifications to reduce the overuse injury risk.

Arch support systems

Arch support systems help the foot by storing and releasing elastic energy and preventing arch collapse during high loading [102]. Foot arches can be classified as flat/low, normal, or high [103]. Within the three groups, low-arched runners may exhibit greater eversion movement and velocity than high-arched runners [104]. Arch support systems can be integrated into the midsole or achieved through custom-made insoles shaped into the foot arch [105].

Our review found seven articles, four of which examined the effect of arch support systems on running biomechanics with a covariate (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 5). Two studies used foot arch height as the covariate, and they found that high-arched runners reduced vertical GRF loading rates in a shoe without arch support, while low-arched runners reduced loading rates in a shoe with arch support. However, both foot arch types experienced reduced rearfoot eversion in a motion control shoe [106]. With a subset of this data, no changes in rearfoot eversion movements for runners with different foot arch types were observed when running in shoes with and without arch support systems during a prolonged run [107]. One article accounted for the runner’s foot strike pattern and found that rearfoot strikers decreased ground contact time in footwear without arch support [108]. In contrast, forefoot strikers reduced contact time in a shoe with arch support [108]. The same study found that forefoot strikers in minimal footwear reduced vertical GRF loading rates, but rearfoot strikers did not. Furthermore, training for three months in footwear with a custom-made arch support system reduced rearfoot eversion [105].

We identified three articles investigating the effect of arch support systems on BRFs without considering covariates. A study involving female runners found no effect of arch support on vertical GRF loading rates, peak rearfoot eversion angles, and peak femur rotation angles [46]. Another study also found unchanged rearfoot eversion movements (peak eversion angle and rearfoot inversion at initial ground contact) and knee abduction angles when runners with AT symptoms ran in footwear with and without arch support [109]. Although BRFs were unchanged, a 92% relief of AT symptoms was reported when wearing an insole with custom-made arch support. Finally, one study found unchanged ground contact times when running in midsoles with 20 mm and 24 mm high arch support elevations [101].

The limited literature suggests that arch support systems can potentially reduce BRFs for runners with different arch heights and a history of PF. Runner’s foot strike pattern might be considered when individualising arch support systems. When individualising arch support systems to minimise BRFs associated with PFPS (ground contact time) and PF (vertical GRF loading rate), forefoot strikers might benefit from less arch support than rearfoot strikers. Moreover, customised arch support systems enhance comfort perception without changes in peak knee abduction angles and vertical GRF loading rates. Arch support might reduce rearfoot eversion movements and thus have the potential for individualisation for runners with a history of AT, TSF, and MTSS. BRFs related to ITBS (peak femur rotation angle and peak knee abduction angles) seem to change marginally and unsystematically with arch support.

Heel flares

Flares can be described as a projection of the midsole and outsole extending beyond the upper [25]. Flares can be placed medially or laterally along the outline of the midsole and were introduced to alter the rearfoot eversion angle, thus increasing foot stability by changing the ankle joint moment arm [110,111,112].

After examining all articles, we identified five matching our inclusion criteria (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 6). None of these articles investigated the effect of a covariate.

Concerning BRFs, one study altered the medial heel flare from 0° to 15°, and 30°. The 2D video-based analysis indicated higher rearfoot eversion movement in footwear without heel flares [81]. In the same study, runners running in shoes with the most extreme medial heel flare modification had, on average, lower rearfoot eversion range of motion than in shoes with less or without heel flares. These findings were supported by other research showing that footwear with heel flares can reduce the magnitude of rearfoot eversion across the entire stance phase but does not seem to reduce vertical GRF loading rates [110, 112, 113]. On the contrary, one study with only five runners did not show that rearfoot eversion movement (at initial ground contact, peak, and range of motion) changes when running in footwear with different heel flares [111]. From a perception perspective, heel flares can improve perceived foot stability [112].

None of the articles considered covariates (e.g., foot strike pattern), highlighting future research potential. Although we found diverse results regarding rearfoot eversion movement, midsoles with heel flares might reduce BRFs linked to AT, TSF, or MTSS. Based on the very limited body of literature, midsoles with heel flares are insufficient for reducing vertical GRF loading rates, and individualised heel flares may not target runners with a history of PF.

Crash pads

Crash pads are elements incorporated into the posterior-lateral midsole using softer foams, segmented geometries, air pockets, or gel-filled patches. Crash pads in the rearfoot area aim to attenuate the GRF and reduce the GRF’s lever arm to the ankle joint [114].

After assessing articles for their eligibility, we identified three articles matching our inclusion criteria (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 7). Out of the three articles, one study considered the fatigue status of female runners as a covariate. As the runners’ fatigue increased, wearing footwear without crash pads increased vertical GRF loading rates compared to the non-fatigue state. However, running in footwear with crash pads maintained consistent vertical GRF loading rates, even as the runners’ fatigue increased. [115]. The same study found no effect of fatigue on the peak free moment amplitude.

When not considering covariates, two studies found reduced rearfoot inversion angles at touchdown in footwear with smaller compared to larger crash pad dimensions. However, there were no differences in peak rearfoot eversion angles during the stance phase of running and unsystematic changes in vertical GRF loading rates [114, 116]. Crash pad modifications did not affect the peak free moment amplitude, ground contact time, and rearfoot eversion range of motion [114,115,116]. Changes in crash pad dimensions do not seem to influence the runner’s comfort perception [114]. However, they may provide an essential tool for individualisation to tune midsole cushioning properties without increasing stack height which has been shown to increase rearfoot eversion [81].

Fatigue seems to be a relevant covariate when individualising crash pads to minimise vertical GRF loading rates, thus, might lower the risk of developing PF. However, runners with a history of TSF might need other individualised FDF to lower peak free moment amplitudes. Increasing crash pad height might help runners with plantar fascia complaints by lowering the vertical GRF loading rates. Runners with a history of AT, TSF, or MTSS might benefit from crash pads by reducing rearfoot eversion movement. Surprisingly, although the FDF aimed at attenuating the peak impulse, we have identified only two studies that have analysed vertical GRF loading rate as BRF.

Other footwear design features

Rocker

Rockers in running shoes aim to reduce the strain on the toes, foot, and ankle by altering the midsole’s curvature in the anterior–posterior direction, positioning the apex near the metatarsal heads, and enhancing the midstance-to-push-off transition for a smoother heel-to-toe rolling motion [117].

Each of the three identified articles considered a covariate in their analysis (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 8). One study considered running speeds as a covariate. Although running at higher speeds increases the vertical GRF loading rate, no changes in GRF loading rates were observed between shoes with and without rocker [118]. Two studies considered the foot strike pattern and found that a toe spring starting closer to the midfoot reduced pressure in the forefoot compared to a standard rocker placed at 65% of the shoe length [119]. However, runners perceived the traditional rocker as more comfortable. When compared to shoes without rockers, one study found that a rocker shoe reduced ground contact time but did not affect knee flexion angles at initial ground contact [120].

The number of studies addressing injury-specific BRFs and the effects of rocker designs is limited. Rockers involve different levels of FDF (stack height, cushioning), and therefore it is difficult to assign a specific feature to a specific BRF. More research is needed to understand if certain covariates can cause a specific change in BRFs and how different FDFs that combine a rocker design need to be tuned for individualisation.

Outsole profile

A shoe’s outsole interacts with the running surface and requires attributes like traction, waterproofness, durability, and puncture resistance [121]. Material robustness might be related to running shoe comfort, and high traction might increase free moment amplitudes associated with TSF [122].

After assessing all articles for eligibility, we could not identify any articles matching our predefined inclusion criteria (Fig. 4). Future studies might use wearable sensors or markerless tracking systems to analyse runners wearing shoes with different outsole profiles on natural surfaces.

Flex grooves

Flex grooves and zones are included in outsoles and midsoles to enhance flexibility, facilitating metatarsophalangeal joint movement and shock absorption. Their placement is essential for the joint’s variable axis and should be individualised based on foot measurements. Recent 3D measurements indicate significant variation, underscoring the need for personalized flexible zones [123].

Our literature search identified one article matching our predefined inclusion criteria (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 9). This article considered running speed as a covariate. In this study, the midsole flexibility was altered by cuts with different orientations at the heel region. Although interaction effects were only marginal when jogging or running in footwear with different groove designs, a 10% lower vertical GRF loading rate was observed in the midsole with grooves compared to the midsoles without grooves at the rearfoot [124]. Interestingly, footwear with greater flexibility is perceived as more comfortable than midsoles with less flexibility [125, 126].

While there is limited research on the impact of flex grooves on relevant BRFs for common RRI, one identified article found that they can reduce vertical GRF loading rates, suggesting that flex grooves may be customised for runners with PF.

Longitudinal bending stiffness

The longitudinal bending stiffness can impact the running economy by optimising energy return and kinematics of the metatarsal joint and force application [127,128,129,130,131]. The bending stiffness can be modified by adding reinforcement materials or changing the geometry of stiff midsole compounds. The optimal bending stiffness depends on factors such as running speed and body weight [128, 132].

Our literature search identified eleven articles, of which four accounted for a covariate (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 10). All four articles considered running speed as a covariate. None of these articles found a significant interaction effect on BRFs when running in footwear with different longitudinal bending stiffness at different running speeds [133,134,135,136]. Independent of running speed, studies reported reduced ground contact times when running in shoes with lower bending stiffness, while one article found unchanged ground contact times [136].

When not considering covariates, three studies found no changes in the GRF braking impulse when running in shoes with different bending stiffness [135, 137, 138]. On the contrary, a reduction in GRF braking impulse in footwear with higher bending stiffness was found in one study [134]. Eight articles found a reduction in the ground contact time [130, 133,134,135, 137,138,139], and two found unchanged ground contact times [134, 140] when running in midsoles with lower bending stiffness. Although studies found lower vertical GRF loading rates [140] and increased comfort perception [135] when athletes ran in more flexible than stiffer midsoles, the relationship between BRFs and injury development when altering the longitudinal bending stiffness has not been sufficiently studied yet, but first studies have evolved showing that bones stress injuries might increase when switching to footwear with carbon fibre plates [18].

The limited body of literature suggests that fitting longitudinal bending stiffness to the runner’s needs may help with treating PFPS. While reduced bending stiffness can reduce ground contact time, higher stiffness can reduce ground reaction force braking impulse. However, injury prevention and reinjury risk minimisation under the light of different longitudinal bending stiffness has been insufficiently investigated. Furthermore, flexible midsoles with lower longitudinal bending stiffness might reduce vertical GRF loading rates and potentially help runners with a history of PF.

The upper

The running shoe upper is comprised of a textile fabric and lacing system that couple the foot and shoe, with reinforcement materials used for stability and breathability. An optimal fit depends on individual foot morphology, while insufficient coupling can negate benefits from other design features. Moreover, excessive pressure can affect comfort by restricting blood supply, making individualisation important [141]. Since foot dimensions differ across sexes, ages, and ethnic origins, individualised upper bears great potential for individualisation [142].

Upper fabric

Our systematic literature search identified two articles investigating the effect of different upper modifications (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 11). None of the articles considered covariates [53, 143].

The data indicates that a soft-sewed structured fabric reduces knee abduction angles and vertical GRF loading rates compared to a minimalist heat fusion fabric. Furthermore, the ground contact time was reduced when running in minimalist heat fusion fabric.

The current body of literature is insufficient to give recommendations for upper individualisation concerning the reduction of BRFs. Based on the limited results, upper materials might be individualised to the runner’s preference.

Lacing

Five articles have investigated the effect of lacing on the lower extremity joint biomechanics or subjective comfort perception (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 12).

One of five studies considered the runner’s experience as a covariate. The researchers found that low-level runners perceived an irregularly (skipping eyelets) laced running shoe as more stable and comfortable than high-level runners who preferred a regular high and tight lacing pattern [144].

We identified four studies analysing BRFs without accounting for covariates. According to a study, running shoes with traditional lacing and elastic upper material were perceived as more comfortable than footwear without lacing [145]. When running in shoes with various lacings, two studies found no significant difference in the rearfoot eversion angle at initial contact [145, 146]. The same studies found a reduction in the peak rearfoot eversion angle when running in traditionally laced shoes compared to those without traditional lacing. However, another study systematically changed lacing patterns and could not find any differences in the peak rearfoot eversion angle [147]. Different types of lacing patterns, particularly high- and tightly-laced shoes, have been shown to reduce vertical GRF loading rate at the cost of comfort [144, 148].

Studies analysing BRFs and considering relevant covariates, e.g., foot shape, are required in the future. Notably, no studies have measured the foot-shoe coupling or the relative movement of the foot within the shoe, highlighting the potential for future research to determine individualised fits and their interactions with other FDF. Since peak rearfoot eversion angles and vertical GRF loading rates are reported to be lower when running in tightly and high-laced shoes, runners with a history of MTSS and TSF might target individualised lacing systems.