Have you ever experienced a nagging knee pain that seems to come out of nowhere, without any visible signs of injury or swelling? You’re not alone. Many individuals face the challenge of knee instability or pain without the typical symptoms of inflammation.

This phenomenon can be puzzling and concerning, especially when it affects your mobility and quality of life. Unlike typical knee injuries that present with obvious swelling, cases without accompanying inflammation require careful assessment to identify the underlying cause.

We will explore the various factors that can lead to knee issues without swelling, from ligament injuries to chronic conditions and degenerative changes, and discuss the proper diagnosis and treatment options.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding knee instability without swelling is crucial for proper diagnosis.

- Ligament injuries can cause knee pain without visible swelling.

- Chronic conditions and degenerative changes can lead to knee instability.

- Careful assessment is necessary to identify the underlying cause.

- Various treatment options are available depending on the diagnosis.

Understanding Knee Stability and Its Importance

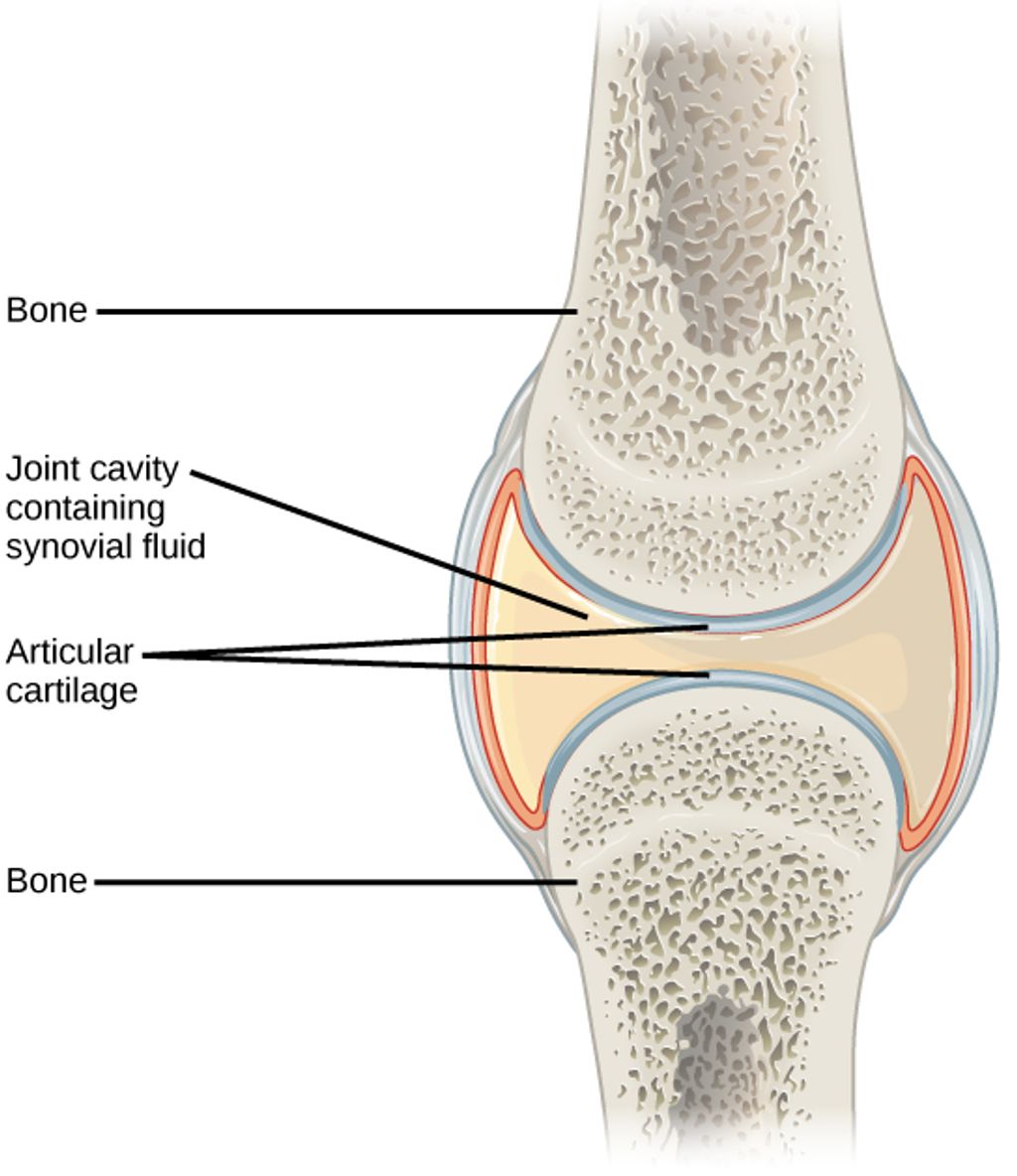

Knee stability, often taken for granted, is fundamental to our ability to move freely and maintain an active lifestyle. The knee joint is one of the most complex in the human body, relying on a delicate balance of structures to maintain proper stability and function. As we explore the intricacies of knee stability, it becomes clear that understanding its anatomy and importance is crucial for appreciating its role in our daily lives.

The Anatomy of a Stable Knee

The stability of the knee joint is maintained by a combination of its shape and various supporting structures. The four major ligaments – the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) – serve as primary stabilizers. Additionally, the shape of the femoral condyles and menisci contributes significantly to knee stability by creating a congruent surface that helps distribute weight and absorb shock during movement.

Secondary stabilizers include the posteromedial and posterolateral capsular components, the iliotibial tract, and the surrounding musculature that provides dynamic support during activity. The intricate network of ligaments, tendons, muscles, and cartilage works in harmony to allow for smooth, pain-free movement.

How Knee Stability Affects Daily Function

Proper knee stability is crucial for everyday activities such as walking, climbing stairs, and sitting. Even minor instability can potentially lead to significant functional limitations and compensatory movement patterns. When the knee is functioning properly, these structures work together seamlessly, maintaining the joint’s integrity during various activities.

As highlighted by experts, “Understanding the complex anatomy of the knee is essential for diagnosing the specific cause of instability when swelling is absent.” This knowledge is vital for addressing issues related to knee stability effectively.

What Causes Knee Instability Without Swelling?

Several factors contribute to knee instability without swelling, including ligament tears, muscle weakness, and chronic conditions. Knee instability is a complex condition that can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life. Understanding the underlying causes is crucial for developing effective treatment plans.

Ligament Injuries and Tears

Ligament injuries are a common cause of knee instability. These injuries can result from direct or indirect trauma, with “noncontact” mechanisms being the most frequent. Activities involving cutting, twisting, jumping, and sudden deceleration can place excessive stress on the knee ligaments, leading to tears or laxity. For instance, a sudden change in direction during sports can cause a ligament injury without immediate swelling.

Muscle Weakness and Imbalances

Muscle weakness, particularly in the quadriceps and hamstrings, can significantly contribute to knee instability. When these muscles are weak, they fail to provide adequate dynamic support to the knee joint during movement. Imbalances between muscle groups can also alter knee biomechanics, leading to instability even without acute injury or swelling.

Chronic Conditions and Degenerative Changes

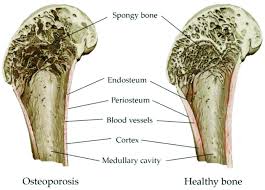

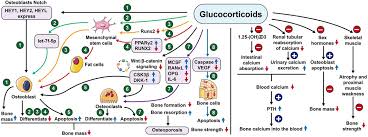

Chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis can gradually erode the joint surfaces and compromise ligament integrity, resulting in progressive instability. Degenerative changes associated with aging or repetitive microtrauma can also affect the knee’s supporting structures, leading to worsening instability symptoms over time. These changes can occur without noticeable swelling, making diagnosis more challenging.

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) Injuries

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) plays a crucial role in maintaining knee stability, and injuries to this ligament can significantly impact knee function. The MCL is attached proximally to the medial femoral condyle and distally to the tibial metaphysis, 4 to 5 cm distal to the medial joint line beneath the pes anserinus insertion. Understanding MCL injuries is essential for diagnosing and treating knee instability effectively.

How MCL Injuries Occur

MCL injuries typically occur from a direct blow to the lateral (outside) aspect of the knee while it’s slightly flexed, creating a valgus force that stresses or tears the medial ligament complex. Isolated MCL injuries happen usually as a result of such direct trauma. When the deforming force includes a rotational component, associated injuries to the cruciate ligaments can occur, complicating the diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosing MCL Instability

Diagnosis of MCL instability involves applying a gentle valgus force to the knee at 15-20 degrees of flexion and comparing the degree of medial joint opening to the uninjured knee. Even a small difference of 5mm in joint opening can indicate substantial structural damage to the MCL, though this may not always be accompanied by visible swelling or significant pain. This diagnostic approach helps in assessing the severity of the MCL injury.

Treatment Options for MCL Injuries

Treatment for MCL injuries is typically conservative, beginning with rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) during the first 48 hours following injury. Physical therapy focusing on strengthening the muscles around the knee joint is crucial for recovery from MCL tears and preventing future instability. Most isolated MCL injuries heal well with conservative treatment, allowing patients to return to normal activities within approximately 6 weeks. However, chronic MCL insufficiency can occur, especially in conjunction with other ligament injuries, requiring a more comprehensive treatment approach.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Damage

Understanding ACL damage is crucial for diagnosing and treating knee instability, which can manifest without noticeable swelling. The ACL is a critical component of the knee joint, providing stability and support during various activities.

The ACL is the primary restraint to anterior translation of the tibia on the femur and to hyperextension. It also functions as a secondary restraint to varus or valgus angulation at full extension and resists internal and external rotation at nearly full extension. Damage to this ligament can lead to significant knee pain and instability, affecting an individual’s ability to perform daily activities and participate in sports.

Mechanisms of ACL Injury

ACL injuries most commonly occur during non-contact situations involving sudden deceleration, pivoting, or landing from a jump with the knee in a vulnerable position. These movements can cause a sudden strain on the ACL, leading to tears or complete ruptures.

Recognizing ACL Instability Without Swelling

Unlike typical ACL tears that present with immediate swelling, some partial tears or chronic ACL insufficiency can manifest primarily as instability without significant effusion. Patients with ACL instability often describe a sensation of the knee “giving way” during pivoting activities. The Lachman test and pivot shift test are reliable clinical examinations for assessing ACL instability.

Conservative vs. Surgical Management

The management of ACL injuries depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, activity level, degree of instability, and willingness to modify activities. Conservative management focuses on strengthening the muscles around the knee, particularly the hamstrings. Surgical reconstruction is typically recommended for young, active patients and those who wish to return to high-demand activities.

| Treatment Approach | Description | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative Management | Strengthening muscles around the knee, particularly hamstrings | Less active patients or those willing to modify activities |

| Surgical Reconstruction | Using autografts or allografts to reconstruct the ACL | Young, active patients and those returning to high-demand activities |

In conclusion, ACL damage is a significant cause of knee instability, and its management requires a comprehensive approach considering the patient’s specific needs and activity level. By understanding the mechanisms of ACL injury and the available treatment options, healthcare providers can offer personalized care to patients suffering from ACL damage.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Issues

Understanding PCL issues is essential for addressing knee instability, particularly in cases where swelling is not a prominent symptom. The PCL is a critical ligament that originates from the medial femoral condyle and inserts into a depression between the posterior aspect of the two tibial plateaux.

PCL Function and Injury

The PCL is composed of two bundles, anterolateral and posteromedial, and serves as the primary restraint to posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur, especially in the mid-range of knee flexion (40-120 degrees). PCL injuries account for approximately 15-20% of all knee ligament injuries and often result from direct trauma to the front of the tibia while the knee is flexed.

- The PCL is crucial for knee stability, particularly during flexion.

- PCL injuries can occur without significant swelling, making diagnosis challenging.

- Direct trauma, such as dashboard injuries in car accidents, is a common cause of PCL tears.

Treatment Approaches for PCL Instability

Treatment for PCL injuries depends on the grade of the tear, associated ligament injuries, and the patient’s activity level and symptoms. Conservative management focuses on quadriceps strengthening to compensate for the lost ligament function, while surgical reconstruction may be necessary for high-grade tears or when conservative treatment fails.

We consider several factors when determining the best treatment approach for PCL instability, including the severity of the injury and the patient’s overall health.

Key treatment considerations include:

- Grade of the PCL tear

- Presence of associated ligament injuries

- Patient’s activity level and symptoms

Lateral and Posterolateral Corner Injuries

The knee joint’s stability is significantly influenced by the integrity of its lateral and posterolateral structures. The lateral and posterolateral corner of the knee comprises several important stabilizing structures, including the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), popliteus tendon, popliteofibular ligament, and arcuate ligament.

Anatomy of the Lateral Knee

The LCL originates on the lateral epicondyle of the femur and is attached distally on the fibular head. The posterolateral corner is a complex anatomic region consisting of the popliteus tendon, the popliteofibular ligament, the arcuate ligament, and the posterolateral joint capsule. Understanding this anatomy is crucial for diagnosing and treating injuries to this area.

Diagnosis of Lateral Instability

Diagnosing lateral instability involves a combination of clinical examination and sometimes additional diagnostic tests. The varus stress test at both full extension and 15 degrees of flexion is crucial for assessing lateral instability. Increased external rotation of the tibia relative to the femur at 30 degrees of knee flexion is characteristic of isolated posterolateral instability.

Management Strategies

Early surgical intervention is often recommended for posterolateral corner injuries, as these structures have limited healing capacity when treated conservatively. For chronic posterolateral instability, reconstruction rather than repair is typically necessary, using either autograft or allograft tissue to restore stability. Rehabilitation following surgery is typically more prolonged and cautious than for isolated cruciate ligament reconstructions.

We recognize that managing lateral and posterolateral corner injuries requires a comprehensive approach, taking into account the specific nature of the injury and the patient’s overall condition. By understanding the anatomy, diagnosis, and appropriate management strategies, healthcare providers can offer effective treatment options for patients experiencing knee instability due to these injuries.

Other Causes of Knee Instability Without Swelling

The absence of swelling doesn’t rule out knee instability, which can be caused by multiple factors. We will explore some of these causes, including meniscal injuries, patellofemoral issues, and degenerative conditions like arthritis.

Meniscal Injuries

Meniscal tears can cause knee instability without significant swelling, particularly when the tear affects the meniscus’s role in joint congruity. The meniscus is cartilage that cushions the inner side of the knee joint. An injury to this area can lead to pain in the inner knee.

Patients with meniscal injuries often report mechanical symptoms such as catching, locking, or giving way during specific movements. These symptoms can occur even when swelling is minimal or absent.

Patellofemoral Issues

Patellofemoral issues, including maltracking of the patella or patellofemoral pain syndrome, can create a sensation of instability, particularly when ascending or descending stairs. Weakness in the vastus medialis obliquus muscle can contribute to patellofemoral instability without causing visible swelling in the knee joint.

Arthritis and Degenerative Conditions

Osteoarthritis affects more than 32.5 million U.S. adults and can cause progressive joint instability as the articular cartilage deteriorates and joint surfaces become incongruent. Early-stage arthritis may cause instability without noticeable swelling, particularly during weight-bearing activities.

Degenerative changes to the menisci that occur with aging can reduce their stabilizing function without triggering an inflammatory response or swelling. Loose bodies within the joint from cartilage or bone fragments can also cause intermittent locking and instability.

Furthermore, neurological conditions affecting proprioception around the knee can create functional instability despite structurally intact ligaments and minimal inflammation. Understanding these various causes is crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosing Knee Instability When No Swelling Is Present

Diagnosing knee instability without swelling requires a comprehensive approach. We must consider the patient’s history, physical examination findings, and results from diagnostic imaging. The absence of swelling can make diagnosis more challenging, but a thorough evaluation can help identify the underlying causes.

Physical Examination Techniques

A detailed physical examination is crucial in diagnosing knee instability. Special tests such as the Lachman test and pivot shift for ACL injuries, the posterior drawer test for PCL injuries, and varus/valgus stress tests for collateral ligament injuries are essential. Comparing the affected knee to the uninjured side helps detect subtle differences in laxity that might indicate ligament insufficiency.

For instance, the Lachman test is particularly useful for assessing ACL integrity. It involves gently pulling the tibia forward while stabilizing the femur. A significant difference in translation between the two knees can indicate ACL damage.

Imaging and Other Diagnostic Tools

Advanced imaging techniques, particularly MRI, play a vital role in diagnosing ligament, meniscal, and cartilage injuries when swelling is absent. MRI provides detailed images of soft tissue structures, helping to identify tears or other damage. Stress radiographs can also quantify the degree of instability in collateral ligament injuries.

| Diagnostic Tool | Use in Knee Instability Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| MRI | Detailed imaging of soft tissues, including ligaments and menisci |

| Stress Radiographs | Quantifying instability in collateral ligament injuries |

| Arthroscopy | Direct visualization of intra-articular structures and potential treatment |

When to Seek Medical Attention

Patients should seek medical attention if they experience recurrent episodes of the knee “giving way,” inability to fully trust the knee during activities, or when instability interferes with daily function. For more information on related issues, you can visit https://kneehurt.com/causes-and-treatments-for-knee-pain-clicking/. Delayed diagnosis can lead to secondary injuries and accelerated joint degeneration, making timely medical evaluation crucial.

Conservative Treatment Approaches

The initial approach to treating knee instability without swelling typically involves conservative treatment methods. We focus on addressing the root causes of instability and improving knee function through non-surgical means.

Strengthening and Rehabilitation

Physical therapy forms the cornerstone of conservative treatment for knee instability. We emphasize strengthening the muscles that dynamically stabilize the knee, particularly the quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip abductors. Proprioceptive training is also essential for improving the body’s awareness of knee position and movement, helping to compensate for ligamentous instability through enhanced neuromuscular control.

Rehabilitation protocols typically progress from basic range of motion exercises to closed-chain strengthening activities and eventually sport-specific training for those returning to athletic activities. This structured approach helps in restoring knee stability and function.

Supportive Devices

Bracing and supportive devices can provide additional stability for knees experiencing instability. Functional knee braces may improve joint position sense and limit excessive movement, though their effectiveness can vary among patients and conditions. For patients with instability related to osteoarthritis, unloader braces can be particularly helpful by redistributing forces away from the affected compartment of the knee.

Modifying Activities

Activity modification is often necessary to prevent symptom exacerbation. We advise patients to avoid high-risk movements that trigger instability episodes. Low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, and elliptical training can maintain cardiovascular fitness while minimizing stress on an unstable knee. For patients with instability related to arthritis, weight management is crucial as each pound of weight loss reduces stress on the knee joint by approximately four pounds during walking.

Conservative treatment success depends largely on patient compliance with home exercise programs and willingness to modify activities that provoke instability. By adopting these strategies, individuals can effectively manage knee instability without swelling and improve their overall knee health.

Surgical Interventions for Persistent Knee Instability

When knee instability persists despite conservative management, surgical intervention may be necessary to restore stability and function. Surgical techniques have evolved to address various causes of knee instability, offering patients a range of options tailored to their specific needs.

Reconstructive Procedures

Surgical reconstruction for knee instability often involves repairing or replacing damaged ligaments. Modern techniques primarily use autografts (the patient’s own tissue) or allografts (donor tissue) to replace damaged ligaments. The choice of graft material depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, activity level, and previous surgeries.

- Autografts: Using the patient’s own tissue, such as the patellar tendon or hamstring tendons, for ligament reconstruction.

- Allografts: Utilizing donor tissue for patients who may not be suitable for autografts or prefer this option.

The surgical technique requires precise placement and tensioning of the graft, avoidance of impingement, and adequate fixation to ensure successful outcomes.

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Post-surgical rehabilitation is crucial for optimal outcomes. Rehabilitation typically begins with early range of motion exercises and progresses to strength training and sport-specific activities. The recovery process can vary based on the specific procedure and individual healing factors.

Generally, full recovery and return to sports or demanding activities take 6-12 months following major ligament reconstruction. Patients should be prepared for a gradual return to their normal activities under the guidance of a healthcare professional.

Expected Outcomes and Timeline

Long-term success rates for ligament reconstruction surgeries range from 80-95% for restoring knee stability. However, outcomes can be influenced by factors such as age, activity level, and associated injuries. It’s essential for patients to have realistic expectations about surgical outcomes, understanding that while stability can be significantly improved, the knee may not return to its pre-injury state.

By understanding the available surgical interventions and what to expect during recovery, patients can make informed decisions about their treatment options for knee instability.

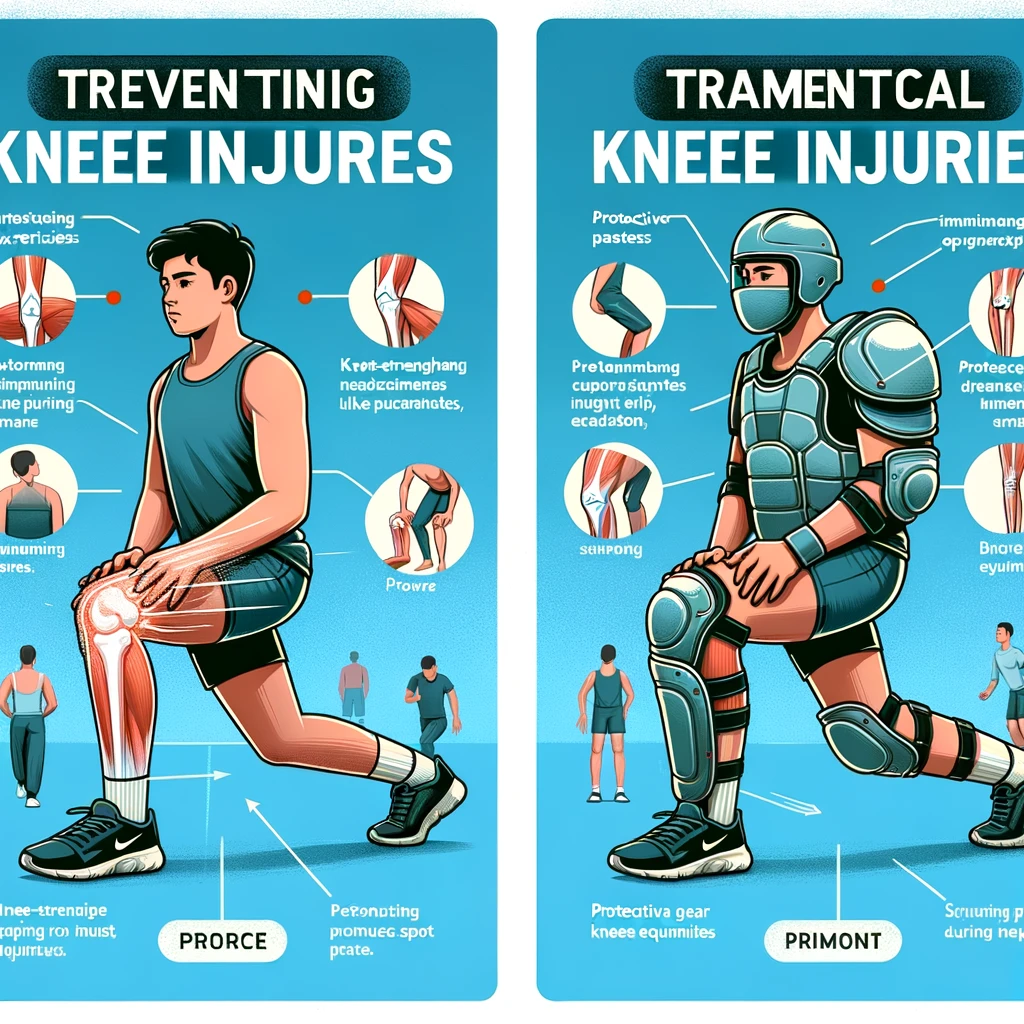

Preventing Future Episodes of Knee Instability

A proactive approach to managing knee health involves addressing modifiable risk factors and adjusting activities to prevent instability episodes. Maintaining an optimal weight is crucial, as excess weight significantly increases stress on the knee joint. For every pound of weight lost, the knee joint forces are reduced by approximately four pounds during walking, thereby decreasing the risk of knee pain and instability.

Engaging in regular strength training that focuses on the quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip muscles is also vital. This training provides dynamic stability to the knee, compensating for any ligamentous laxity or degenerative changes. Furthermore, using proper technique during sports and exercise, especially for movements involving cutting, pivoting, jumping, and landing, can significantly reduce the risk of knee injury.

Other preventive measures include wearing appropriate footwear with good support and proper fit, which can improve lower extremity alignment and reduce abnormal forces on the knee. For individuals with known ligament insufficiency, preventive bracing may be beneficial during high-risk activities. Additionally, incorporating low-impact activities like swimming and cycling into one’s fitness routine can help maintain fitness while reducing repetitive stress on the knee joint.

Maintaining good flexibility through regular stretching and proper warm-up routines before activities can also reduce the risk of knee injury. For patients with arthritis-related instability, adopting an anti-inflammatory diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants may help manage inflammation and symptoms. Lastly, regular medical care and adherence to prescribed treatment regimens are essential for managing underlying conditions that contribute to knee instability.

FAQ

What are the common causes of knee pain and instability?

We find that knee pain and instability can be caused by various factors, including ligament injuries, muscle weakness, and degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis. Activities that put stress on the knee joint, like sports, can also contribute to these issues.

How is knee instability diagnosed when there’s no swelling?

Diagnosing knee instability without swelling involves a physical examination, imaging tests like X-rays or an MRI, and assessing the knee’s range of motion. We also consider the patient’s medical history and activity level to make an accurate diagnosis.

Can knee instability be treated without surgery?

Yes, we often recommend conservative treatment approaches, such as physical therapy, bracing, and modifying activities to alleviate knee instability. These methods can be effective in managing symptoms and improving knee function.

What role do ligaments play in knee stability?

Ligaments, including the ACL, PCL, MCL, and lateral ligaments, provide crucial support to the knee joint. Injuries to these ligaments can lead to knee instability, and we may recommend reconstructive surgery in severe cases.

How can I prevent future episodes of knee instability?

To prevent knee instability, we suggest maintaining a healthy weight, engaging in exercises that strengthen the surrounding muscles, and using proper techniques during sports and activities. Wearing supportive devices like knee braces can also help.

What is the typical recovery time after knee surgery?

The recovery time after knee surgery varies depending on the type of procedure and individual factors. Generally, we can expect several months of rehabilitation, during which we’ll guide you through a structured recovery program to restore knee function and strength.

Can osteoarthritis cause knee instability?

Yes, osteoarthritis can contribute to knee instability by causing degenerative changes in the joint, including cartilage loss and ligament laxity. We can help manage osteoarthritis symptoms and related knee instability through a combination of conservative and surgical treatments.